James Gethi and one of the crops closest to his heart – maize. He also has a soft spot for hardy crop varieties that survive harsh and unforgiving drylands, such as Machakos, Kenya, where this June 2011 photo of him with drought-tolerant KARI maize was taken.

As we tell our closing stories on our Sunset Blog, in parallel, we’re also catching up on the backlog of stories still in our store from the time GCP was a going concern. Our next stop is Kenya, and the narrative below is from 2012, but don’t go away as it is an evergreen – a tale that can be told at any time, as it remains fresh as ever. At that time, and for the duration of the partnership with GCP, the Food Crops Research Institute of the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation (KALRO) was then known as the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI), and we shall therefore stay with this previous name in the story. KARI was also the the name of the Kenyan institute at the time when James Gethi (pictured) left for a sabbatical at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT by its Spanish acronym). On to the story then, and please remember we’re travelling back in time to the year 2012.

“I got into science by chance, for the fun of it,” muses James, maize breeder and former GCP scientist “With agricultural school promising a flight to overfly the country’s agricultural areas– this was an interesting prospect for a village guy. ‘This could be fun’, I thought!”

And it turned out to be a chance well worth taking. His first step was getting the requisite education. And so he armed himself with a BSc in Agriculture from the University of Nairobi, Kenya, topped with a Master’s and PhD in Plant Breeding from the University of Alberta (Canada) and Cornell University (USA), respectively. Beyond academics, in the course of his crop science career, James has developed 13 crop varieties, that included maize and cassava, published papers in numerous peer-reviewed papers (including the 2003 prize for Best paper in the field of crop science in the prestigious Crop Science journal. And in leadership, James headed the national maize research programme in his native Kenya. These are just a few of the achievements James has garnered in the course of his career, traversing and transcending not only the geographical frontiers initially in his sights, but also scientific ones, reaching professional heights that perhaps his younger self might never have dreamt possible.

As a Research Officer at KARI, a typical day sees James juggling his time between hands-on research (developing maize varieties resistant to drought, field and storage pests) and project administration, coordinating public–private partnerships and the maize research programme at both institutional and country level. What motivates the man shouldering much of the responsibility for the buoyancy of his nation’s staple crop? James explains, “Making a difference by providing solutions to farmers. That’s my passion and that’s what makes me get up in the morning and go to work. It’s hugely satisfying!”

Without GCP, I would not be where I am today as a scientist… [it] gave me a chance to work with the best of the best worldwide… You develop bonds and understanding that last well beyond the life of the projects.”

Rapid transitions: trainee to trainer to leader

It was this passion and unequivocal dedication to his vocation – not to mention a healthy dollop of talent – that GCP was quick to recognise back in 2004, when James first climbed aboard the GCP ship. Like a duck to water, he proceeded to engage in all manner of GCP projects and related activities, steadily climbing the ranks from project collaborator to co-Principal Investigator and, finally, Principal Investigator in his own right, leading a maize drought phenotyping project. Along the way, he also secured GCP Capacity building à la carte and Genotyping Support Service grants to further the maize research he and his team were conducting.

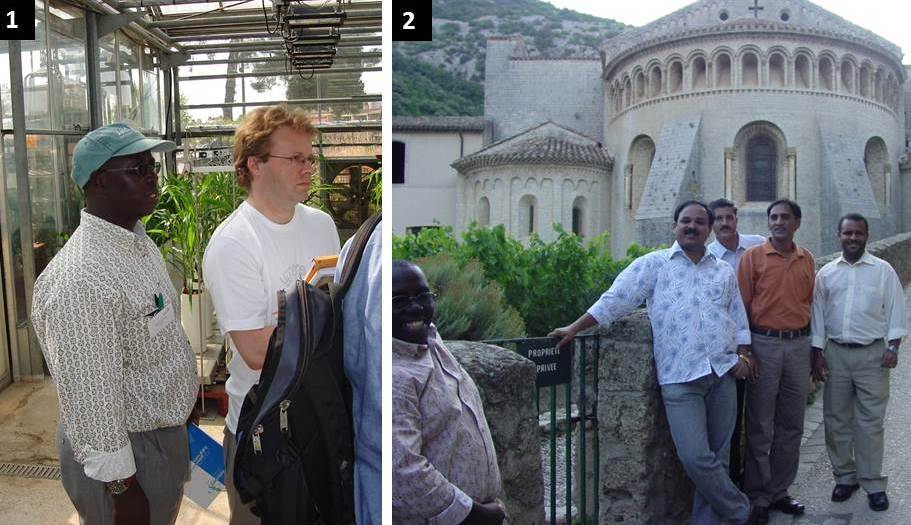

FLASHBACK: At a GCP drought phenotyping course in mid-2006 at Montpellier, France. (1) James (left) pays keen attention during one of the practical sessions. (2) In the spirit of “All work and no play, etc”, taking a break from the course to take in some of the sights with colleagues. Clearly, James, “the guy from the village” is anything but a dull boy! Next to James, second left, is BM Prasanna, currently leader of CIMMYT’s maize programme.

From trainee to trainer and knowledge-sharer: James (behind the camera) training KARI staff on drought phenotyping in June 2009 at Machakos, in Kenya’s drylands.

The GCP experience, James reveals, has been immensely rewarding: “Without GCP, I would not be where I am today as a scientist,” he asserts. And on the opportunity to work with a capable crew beyond national borders, as opposed to operating as a solo traveller, he says: “GCP gave me a chance to work with the best of the best worldwide, and has opened up new opportunities and avenues for collaboration between developing-country researchers and advanced research institutes, creating and cementing links that were not so concrete before. This has shown that we don’t have to compete with one another; we can work together as partners to derive mutual benefits, finding solutions to problems much faster than we would have done working alone and apart from each other.”

The links James has in mind are not only tangible but also sustainable: “You develop bonds and understanding that last well beyond the life of the projects,” James enthuses, citing additional professional engagements (the African Centre for Crop Improvement in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and the West Africa Centre for Crop Improvement, have both welcomed James and his team into their fold), as well as firm friendships with former GCP project colleagues as two key take-home benefits of his interaction with the Programme. These new personal and professional circles have fostered a happy home for dynamic debates on the latest news and views from the crop-science world, and the resultant healthy cross-fertilisation of ideas, James affirms.

Reflecting on what he describes as a ‘mentor’ role of GCP, and on the vital importance of capacity building in general, he continues: “By enhancing the ability of a scientist to collect germplasm, or to analyse that germplasm, or by providing training and tips on how to write a winning project proposal to get that far in the first place, you’re empowering scientists to make decisions on their own – decisions which make a difference in the lives of farmers. This is tremendous empowerment.”

Another potent tool, says James, is the software made available to him through GCP’s Integrated Breeding Platform (IBP), which is a handy resource package to dip into for – among other things – analysing data and selecting the right varieties at the right time. The next step for IBP, he feels, should be scaling up and aiming for outreach to the wider scientific community, forecasting that such a step could bring nothing but success: “The impacts could be enormous!” he projects, with a palpable and infectious enthusiasm.

People… don’t eat publications, they eat food… I’m not belittling knowledge, but we can do both”

Fast but not loose on the R&D continuum: double agent about?

For James, outreach and impacts are not limited to science alone. In parallel with his activities in upstream genetic science, James’ efforts are equally devoted to the needs of his other client base-–the development community and farmers. For this group, James’ focus is on putting tangible products on the table that will translate into higher crop yields and incomes for farmers. Yet whilst products from any highly complex scientific research project worth its salt are typically late bloomers, often years in the making on a slow burner as demanded by the classic linear R&D view that research must always precede development, adaptation and final adoption, James has been quick to recognise that actors in the world of development and the vulnerable communities they serve do not necessarily have this luxury of time.

August 2008: a huge handful, and more where that came from in Kwale, Kenya. This farmer’s healthy harvest came from KARI hybrids.

His solution for this challenge? “Sitting where I sit, I realised from very early on that if I followed the traditional linear scientific approach, my development clients would not take it kindly if I still had no products for them within the three-year lifespan of the project. The challenge then was to deliver results for farmers without compromising or jeopardising their integrity or the science behind the product,” he recalls. In the project he refers to – a GCP-funded project to combat drought and disease in maize and rice – James applied a novel double-pronged approach to get around this seeming conundrum of the need for sound science on the one hand, and the need for rapid results for development on the other hand. Essentially, he simultaneously walked on both tracks of the research–development continuum.

The project – led by Rebecca Nelson of Cornell University and with collaborators including James’ team at KARI (leading the maize component), the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), researchers in Asia, as well as other universities in USA – initially set out with the long-term goal of dissecting quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for rice and maize with a view to combating drought and disease in these crops. Once QTLs were dissected and gene crosses done, James and his team went about backcrossing these new lines to local parental lines, generating useful products in the short term. The results, particularly given the limited resources and time invested, have been impressive, with seven hybrid varieties developed for drylands and coastal regions having been released in Kenya by 2009, and commercialised from 2010.

James and his colleagues have applied the same innovative approach to other GCP projects, grappling to get a good grasp of the genetic basis of drought tolerance, whilst also generating intermediate products for practical use by farmers along the way. James believes this dual approach paves the way for a win-win situation: “People on the ground don’t eat publications, they eat food,” he says. “As we speak now, there are people out there who don’t know where their next meal will come from. I’m not belittling knowledge, but we can do both – boiled maize on the cob and publications on the boil. But let’s not stop at crop science and knowledge dissemination – let’s move it to the next level, which means products,” he challenges, adding: “With GCP support, we were able do this, and reach our intended beneficiaries.”

It is perhaps this kind of vision and inherent instinct to play the long game that has taken James this far professionally, and that will no doubt also serve him well in the future.

As our conversation comes to a close, we ask James for a few pearls of wisdom for other young budding crop researchers eager to carve out an equally successful career path for themselves, James offers “Form positive links and collaborations with colleagues and peers. Never give up; never let challenges discourage you. Look for organisations where you can explore the limits of your imagination. Stay focused and aim high, and you’ll reach your goal.”

Upon completion of his ongoing sabbatical at CIMMYT in Zimbabwe, where he is currently working on seed systems, James plans to return to KARI, armed with fresh knowledge and ready to seize – with both hands – any promising collaborative opportunities that may come his way .

Certainly, prospects look plentiful for this ‘village lad’ in full flight, and who doesn’t look set to land any time soon!

In full flight – Montpellier, Brazil, Benoni, Bangkok, Bamako, Hyderabad… our boy voyaged from the village to Brazil and back, and far beyond that. Sporting the t-shirt from GCP’s Annual Research Meeting in Brazil in 2006, which James attended, he also attended the same meeting the following year, in Benoni, South Africa, in 2007, when this photo was taken. James is a regular at these meetings which are the pinnacle on GCP’s calendar (http://bit.ly/I9VfP4). But he always sings for his supper and is practically part of the ‘kitchen crew’, but just as comfortable in high company. For example, he was one of the keynote speakers at the 2011 General Research Meeting (see below).

Links:

- Briefs on James’ projects (2009): Drought phenotyping of the maize reference set, page 17 | Capacity-building à la carte p 56

- Update on work from Genotyping Support Service grant, 2008

- Disease resistance project in which James was a collaborator

- Maize – Blogposts | Research Initiative | InfoCentre | Research products | Book chapter on drought phentoyping | Slides