One of the greatest challenges of our time is growing more crops to feed more people, but using less water

Sorghum is one of the most ‘efficient’ crops in terms of needing less water and nutrients to grow. And although it is naturally well-adapted to sun-scorched drylands, there is still a need to improve its yield and broad adaptability in these harsh environments. In West Africa, for example, while sorghum production has doubled in the last 20 years, its yield has remained stagnant – and low.

The GCP Sorghum Research Initiative comprises several projects, which are exploring ways to use molecular-breeding techniques to improve sorghum yields, particularly in drylands. All projects are interdisciplinary international collaborations with an original focus on Mali, where sorghum-growing areas are large and rainfall is getting more erratic and variable. Through the stay-green project, the research has since broadened to also cover Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, Niger and Sudan.

Using molecular markers is new and exciting for us as it will speed up the breeding process. With molecular markers, you can easily see if the plant you’ve bred has the desired characteristics without having to grow the plant and or risk missing the trait through visual inspection.”

What’s MARS got to do with it?

Niaba Témé is a local plant breeder and researcher at Mali’s L’Institut d’économie rurale (IER). He grew up in a farming community on the southern edge of the Sahara Desert, where crops would constantly fail during drier-than-normal seasons.

Niaba Témé

Niaba says these crop failures were in part his inspiration for a career where he could help farmers like his parents and siblings protect themselves from the risks of drought and extreme temperatures.

For the past four years, Niaba and his team at IER have been collaborating with Jean-François Rami and his team at France’s Centre de coopération internationale en recherche agronomique pour le développement (CIRAD), to improve sorghum grain yield and quality for West African farmers. The work is funded by the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture.

“With the help of CIRAD and Syngenta, we have been learning how to use molecular markers to improve breeding efficiency of sorghum varieties more adapted to the variable environment of Mali and surrounding areas which receive less than 600 millimetres of rainfall per year,” he says.

Jean-François Rami

“Using molecular markers is new and exciting for us as it will speed up the breeding process. With molecular markers, you can easily see if the plant you’ve bred has the desired characteristics without having to grow the plant and or risk missing the trait through visual inspection.”

Jean-François Rami, who is the project’s Principal Investigator, has been impressed by the progress made so far. Jean-François is also GCP’s Product Delivery Coordinator for sorghum.

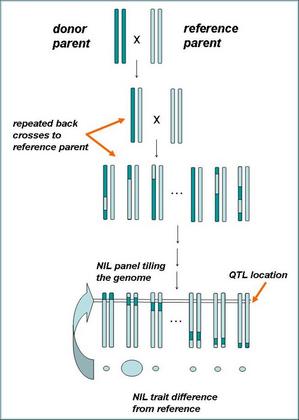

“Since its inception, the project has progressed very well,” says Jean-François. “With the help of the IER team, we’ve been able to develop two bi-parental populations from elite local varieties, targeting two different environments of sorghum cropping areas in Mali. We’ve then been able to use molecular markers through a process called marker-assisted recurrent selection [MARS] to identify and monitor key regions of the genome in consecutive breeding generations.”

The collaboration with Syngenta came from a common perspective and understanding of what approach could be effectively deployed to rapidly deliver varieties with the desired characteristics.

“Syngenta came with their long experience in implementing MARS in maize. They advised on how to execute the programme and avoid critical pitfalls. They offered to us the software they have developed for the analysis of data which allowed the project team to start the programme immediately,” says Jean-François.

Like all GCP projects, capacity building is a large part of the MARS project. Jean-François says GCP has invested a lot to strengthen IER’s infrastructure and train field technicians, researchers and young scientists. But GCP is not the only player in this: “CIRAD has had a long collaboration in sorghum research in Mali and training young scientists has always been part of our mission. We’ve hosted several IER students here in France and we are interacting with our colleagues in Mali either over the phone or travelling to Mali to give technical workshops in molecular breeding. The Integrated Breeding Platform [IBP] has also been a breakthrough for the project, providing to the project team breeding services, data management tools, and a training programme – the Integrated Breeding Multiyear Course [IB–MYC].”

We don’t have these types of molecular-breeding resources available in Mali, so it’s really exciting to be a part of this project… the approach has the potential to halve the time it takes to develop local sorghum varieties with improved yield and adaptability to drought… one of the great successes of the project has been to bring together sorghum research groups in Mali in a common effort to develop new genetic resources for sorghum breeding.”

Back-to-back: more for Mali’s national breeding programme

On the back of the MARS project, Niaba successfully obtained GCP funding in 2010 to carry out similar research with CIRAD and collaborators in Africa at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT).

“In this project, we are trying to enhance sorghum grain yield and quality for the Sudano-Sahelian zone of West Africa using the backcross nested association mapping (BCNAM) approach,” explains Niaba, who is the Principal Investigator of the BCNAM project. “This involves using an elite recurrent parent that is already adapted to local drought conditions. The benefit of this approach is that it can lead to detecting elite varieties much faster.”

A ‘sample’ of the rich mix of international partners in sorghum research: Left to right – Kirsten Vom Brocke (CIRAD), Michel Vaksmann (CIRAD), Mamoutou Kouressy (IER), Eva Weltzien (ICRISAT), Jean-François Rami (CIRAD), Denis Lespinasse (Syngenta), Niaba Teme (IER), Ndeye Ndack Diop (GCP Capacity Building Leader), Ibrahima Sissoko and Fred Rattunde (both from ICRISAT).

Eva Weltzien has been the Principal Scientist for ICRISAT’s sorghum breeding programme in Mali since 1998. She says the project aligned with much of the work her team had been doing, so it made sense to collaborate considering the new range of sorghum genetic diversity that this approach aims to use.

“We’ve been working with Niaba’s team to develop 100 lines for 50 populations from backcrosses carried out with 30 recurrent parents,” explains Eva. “These lines are being genotyped by CIRAD. We will then be able to use molecular markers to determine if any of these lines have the traits we want. We don’t have these types of molecular-breeding resources available in Mali, so it’s really exciting to be a part of this project.”

An annual field day at ICRISAT’s research station at Samanko, Mali. Eva Weltzien (holding sheet of paper) showing Mali’s Minister of Agriculture, Tiemoko Sangare, (in white cap) a graph on the superiority of new guinea race hybrids. Also on display are panicles and seed of the hybrids and released varieties of sorghum in Mali.

Eva says that the approach has the potential to halve the time it takes to develop local sorghum varieties with improved yield and adaptability to drought.

For Jean-François, one of the great successes of the project has been to bring together sorghum research groups in Mali in a common effort to develop new genetic resources for sorghum breeding.

“This project has strengthened the IER and ICRISAT partnerships around a common resource. The large multiparent population that has been developed is analysed collectively to decipher the genetic control of important traits for sorghum breeding in Mali,” says Jean-François.

Plants with this ‘stay-green’ trait keep their leaves and stems green during the grain-filling period. Typically, these plants have stronger stems, higher grain yield and larger grain.”

Sorghum staying green and strong, with less water

In February 2012, Niaba and his colleague, Sidi B Coulibaly, were invited to Australia as part of another Sorghum Research Initiative project they had been collaborating on with CIRAD, Australia’s University of Queensland and the Queensland Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (QDAFF).

“We were invited to Australia for training by Andrew Borrell and David Jordan, who are co-Principal Investigators of the GCP stay-green sorghum project,” says Niaba.

Left to right: Niaba Témé (Mali), David Jordan (Australia), Sidi Coulibaly (Mali) and Andrew Borrell (Australia) visiting an experiment at Hermitage Research Facility in Queensland, Australia.

“We learnt about association mapping, population genetics and diversity, molecular breeding, crop modelling using climate forecasts, and sorghum physiology, plus a lot more. It was intense but rewarding – more so the fact that we understood the mechanics of these new stay-green crops we were evaluating back in Mali.”

It wasn’t all work and there was clearly also time to play, as we can see here., where Sidi Coulibaly and Niaba Témé are visiting the Borrell family in Queensland, Australia.

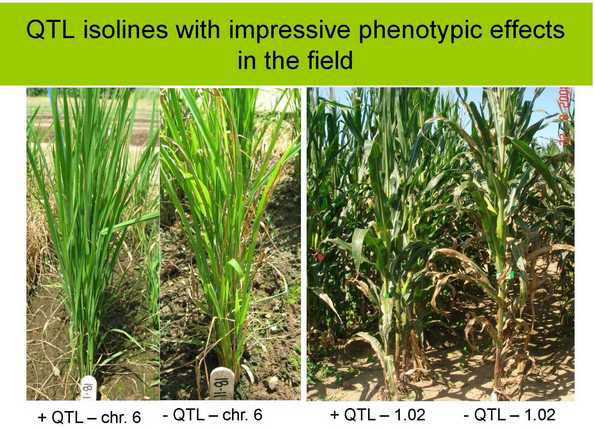

Stay-green is a post-flowering drought adaptation trait that has contributed significantly to sorghum yield stability in northeastern Australia and southern USA over the last two decades.

Andrew has been researching how the drought-resistant trait functions for almost 20 years, including gene discovery. In 2010, he and his colleague, David Jordan, successfully obtained funding from GCP to collaborate with IER and CIRAD to develop and evaluate drought-adapted stay-green sorghum germplasm for Africa and Australia.

“Stay-green sorghum grows a canopy that is about 10 per cent smaller than other lines. So it uses less water before flowering,” explains Andrew. “More water is then available during the grain-filling period. Plants with this ‘stay-green’ trait keep their leaves and stems green during the grain-filling period. Typically, these plants have stronger stems, higher grain yield and larger grain.”

Andrew says the project is not about introducing stay-green into African germplasm, but rather, enriching the pre-breeding material in Mali for this drought-adaptive trait.

The project has three objectives:

- To evaluate the stay-green drought-resistance mechanism in plant architecture and genetic backgrounds appropriate to Mali.

- To develop sorghum germplasm populations enriched for stay-green genes that also carry genes for adaptation to cropping environments in Mali.

- To improve the capacity of Malian researchers by carrying out training activities for African sorghum researchers in drought physiology and selection for drought adaptation in sorghum.

…we have found that the stay-green trait can improve yields by up to 30 percent in drought conditions with very little downside during a good year, so we are hoping that these new lines will display similar characteristics”

Expansion and extension: beyond Mali to the world

Andrew explains that there are two phases to the stay-green project. The project team first focused on Mali. During this phase, the Australian team enriched Malian germplasm with stay-green, developing introgression lines, recombinant inbred lines and hybrids. Some of this material was field-tested by Sidi and his team in Mali.

“In the past, we have found that the stay-green trait can improve yields by up to 30 percent in drought conditions with very little downside during a good year, so we are hoping that these new lines will display similar characteristics,” says Andrew. “During the second phase we are also collaborating with ICRISAT in India and now expanding to five other African countries – Niger and Burkina Faso in West Africa; and Kenya, Sudan and Ethiopia in East Africa. During 2013, we grew our stay-green enriched germplasm at two sites in all these countries. We also hosted scientists from Burkina Faso, Sudan and Kenya to undertake training in Queensland in February 2014.”

A sampling of some of stay-green sorghum partnerships in Africa. (1) Asfaw Adugna of the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR) assessing the genetic diversity of sorghum panicles produced from the GCP collaboration at Melkassa, Ethiopia. (2) Clarisse Barro-Kondombo (left, INERA – Institut de l’environnement et de recherches agricoles , Burkina Faso) and Andrew Borrell (right) visiting a lysimetre facility at ICRISAT’s headquarters in Hyderabad, India, as part of GCP training, in February 2013. (3) Clement Kamau (left, Kenya Agricultural Research Institute [KARI] ) and Andrew Borrell (right) visiting the seed store at KARI, Katumani, Kenya.

Andrew says that the collaboration with international researchers has given them a better understanding of how stay-green works in different genetic backgrounds and in different environments, and the applicability is broad. Using these trial data will help provide farmers with better information on growing sorghum, not just in Africa and Australia, but also all over the world.

“Both David and I consider it a privilege to work in this area with these international institutes. We love our science and we are really passionate to make a difference in the world with the science we are doing. GCP gives us the opportunity to expand on what we do in Australia and to have much more of a global impact.”

We’ll likely be hearing more from Andrew on the future of this work at GCP’s General Research Meeting (GRM) in October this year, so watch this space! Meantime, see slides below from GRM 2013 by the Sorghum Research Initiative team. We also invite you to visit the links below the slides for more information.

Links

Jurandir Magalhães (pictured), or Jura, as he likes to be referred to in informal settings such as our story today, is a cereal molecular geneticist who has been working at the Embrapa Milho e Sorgo centre since 2002. “The centre develops projects and research to produce, adapt and diffuse knowledge and technologies in maize and sorghum production by the efficient and rational use of natural resources,” Jura explains.

Jurandir Magalhães (pictured), or Jura, as he likes to be referred to in informal settings such as our story today, is a cereal molecular geneticist who has been working at the Embrapa Milho e Sorgo centre since 2002. “The centre develops projects and research to produce, adapt and diffuse knowledge and technologies in maize and sorghum production by the efficient and rational use of natural resources,” Jura explains.