Beyond chickpeas to embrace beans, chickpeas, groundnuts and pigeonpeas

As a scientist who comes from the dessicated drylands of the unforgiving Kerio Valley, where severe drought can mean loss of life through loss of food and animals, what comes first is food security… I could start to give something back to the community… It’s been a dream finally coming true.” – Paul Kimurto, Senior Lecturer and Professor in Crop Physiology and Breeding, Egerton University, Kenya

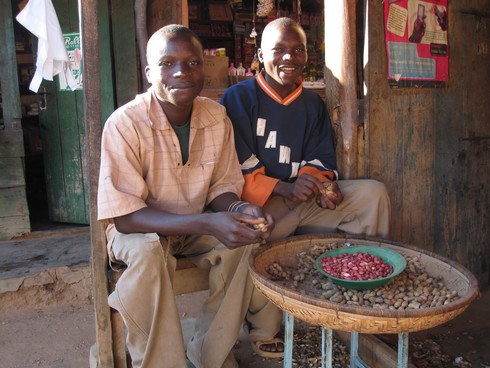

As a son of peasant farmers growing up in a humble home in the Rift Valley of Kenya, agriculture was, for Paul Kimurto (pictured above), not merely a vocation but a way of life: “Coming from a pastoral community, I used to take care of the cattle and other animals for my father. In my community livestock is key, as is farming of food crops such as maize, beans and finger millet.”

Covering some six kilometres each day by foot to bolster this invaluable home education with rural school, an affiliation and ever-blossoming passion for agriculture soon led him to Kenya’s Egerton University.

There, Paul excelled throughout his undergraduate course in Agricultural Sciences, and was thus hand-picked by his professors to proceed to a Master’s degree in Crop Sciences at the self-same university, before going on to obtain a German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) scholarship to undertake a ‘sandwich’ PhD in Plant Physiology and Crop Breeding at Egerton University and the Leibniz Institute for AgriculturalEngineering (ATB) in Berlin, Germany.

… what comes first is food security… offering alternative drought-tolerant crops… is a dream finally coming true!… GCP turned out to be one of the best and biggest relationships and collaborations we’ve had.”

Local action, global interaction

With his freshly minted PhD, Paul returned to Egerton’s faculty staff and steadily climbed the ranks to his current position as Professor and Senior Lecturer in Crop Physiology and Breeding at Egerton’s Crop Sciences Department. Yet for Paul, motivating this professional ascent throughout has been one fundamental factor: “As a scientist who comes from a dryland area of Kerio valley, where severe drought can mean loss of food and animals, what comes first is food security,” Paul explains. “Throughout the course of my time at Egerton, as I began to understand how to develop and evaluate core crop varieties, I could start to give something back to the community, by offering alternative drought-tolerant crops like chickpeas, pigeonpeas, groundnuts and finger millet that provide farmers and their families with food security. It’s been a dream finally coming true.”

And thus one of academia’s true young-guns was forged: with an insatiable thirst for moving his discipline forward by seeking out innovative solutions to real problems on the ground, Paul focused on casting his net wide and enhancing manpower through effective collaborations, having already established fruitful working relationships with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), the (then) Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI) and the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) in earlier collaborative projects on dryland crops in Kenya. It was this strategy that paved the way towards teaming up with GCP, when, in 2008, Paul and his team were commissioned to lead the chickpea work in Kenya for the GCP Tropical Legumes I project (TLI), with local efforts being supported by colleagues at ICRISAT, and friends down the road at KARI undertaking the bean work of the project. Climbing aboard the GCP ship, Paul reveals, was a move worth making: “Our initial engagement with GCP started out as a small idea, but in fact, GCP turned out to be one of the best and biggest relationships and collaborations we’ve had.”

…GCP is people-oriented, and people-driven”

Power to the people!

The success behind this happy marriage, Paul believes, is really quite simple: “The big difference with GCP is that it is people-oriented, and people-driven,” Paul observes, continuing: “GCP is building individuals: people with ideas become equipped to develop professionally.” Paul elaborates further: “I wasn’t very good at molecular breeding before, but now, my colleagues and I have been trained in molecular tools, genotyping, data management, and in the application of molecular tools in the improvement of chickpeas through GCP’s Integrated Breeding Multiyear Course. This has opened up opportunities for our local chickpea research community and beyond, which, without GCP’s support, would not have been possible for us as a developing-country institution.”

Inspecting pod maturity with farmers at Koibatek Farmers Training Centre in Eldama Ravine Division, Baringo County, Kenya, in September 2012. Paul is on the extreme right.

Passionate about his teaching and research work, it’s a journey of discovery Paul is excited to have shares with others: “My co-workers and PhD students have all benefitted. Technicians have been trained abroad. All my colleagues have a story to tell,” he says. And whilst these stories may range from examples of access to training, infrastructure or genomic resources, the common thread throughout is one of self-empowerment and the new-found ability to move forward as a team: “Thanks to our involvement with the GCP’s Genotyping Support Service, we now know how to send plant DNA to the some of the world’s best labs and to analyse the results, as well as to plan for the costs. With training in how to prepare the fields, and infrastructure such as irrigation systems and resources such as tablets, which help us to take data in the field more precisely, we are now generating accurate research results leading to high-quality data.”

The links we’ve established have been tremendous, and we think many of them should be long-lasting too: even without GCP“

Teamwork, international connections and science with a strong sense of mission

Teaming up with other like-minded colleagues from crème de la crème institutions worldwide has also been vital, he explains: “The links we’ve established have been tremendous, and we think many of them should be long-lasting too: even without GCP, we should be able to sustain collaboration with KBioscience [now LGC Genomics] or ICRISAT for example, for genotyping or analysing our data.” He holds similar views towards GCP’s Integrated Breeding Platform (IBP): “IBP is one of the ideas which we think, even after GCP’s exit in December 2014, will continue to support our breeding programmes. My colleagues and I consult IBP regularly for a range of aspects, from markers to protocols to germplasm and the helpdesk, as well as for contacts and content available via the IBP Communities of Practice.” Paul’s colleagues are Richard Mulwa, Alice Kosgei, Serah Songok, Moses Oyier, Paul Korir, Bernard Towett, Nancy Njogu and Lilian Samoei. Paul continues: “We’ve also been encouraging our regional partners to register on IBP – I believe colleagues across Eastern and Central Africa could benefit from this one-stop shop.”

Yet whilst talking animatedly about the greater sophistication and accuracy in his work granted as a result of new infrastructure and the wealth of molecular tools and techniques now available to him and his team, at no point do Paul’s attentions stray from the all-important bigger picture of food security and sustainable livelihoods for his local community: “When we started in 2008, chickpeas were known as a minor crop, with little economic value, and in the unfavoured cluster termed ‘orphan crops’ in research. Since intensifying our work on the crop through TLI, we have gradually seen chickpeas become, thanks to their relative resilience against drought, an important rotational crop after maize and wheat during the short rains in dry highlands of Rift valley and also in the harsh environments of the Kerio Valley and swathes of Eastern Kenya.”

Having such a back-up in place can prove a vital lifeline to farmers, Paul explains, particularly during moments of crisis, citing the 2011–2012 outbreak of the maize lethal necrosis (MLN) disease which wiped out all the maize throughout Kenya’s Bomet County, where Paul, Richard, Bernard and their team had been working on the chickpea reference set. Those farmers who had planted chickpeas – Paul recalls Toroto and Absalom as two such fortunate souls – were food-secure. Moreover, GCP support for infrastructure such as a weather station have helped farmers in Koibatek County to predict weather patterns and anticipate rainfall, whilst an irrigation system in the area is being used by the Kenyan Ministry of Agriculture to develop improved seed varieties and pasture for farmers.

The science behind the scenes and the resultant products are of course not to be underestimated: in collaboration with ICRISAT, Paul and his team released four drought-resistant chickpea varieties in Kenya in 2012, with the self-same collaboration leading to the integration of at least four varieties of the crop using marker-assisted backcrossing, one of which is in the final stages and soon to be released for field testing. With GCP having contributed to the recent sequencing of the chickpea genome, Paul and his colleagues are now looking to up their game by possibly moving into work on biotic stresses in the crop such as diseases, an ambitious step which Paul feels confident can be realised through effective collaboration, with potential contenders for the mission including ICRISAT (for molecular markers), Ethiopia and Spain (for germplasm) and researchers at the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) for germplasm. Paul first established contact with all of these partners during GCP meetings.

By coming together, pooling skills from biotechnology, agronomy, breeding, statistics and other disciplines, we are stronger as a unit and better equipped to offer solutions to African agriculture and to the current challenges we face.”

Links that flower, a roving eye, and the heat is on!

In the meantime, the fruits of other links established since joining the GCP family are already starting to blossom. For example, TLI products such as certified seeds of chickpea varieties being released in Kenya – and in particular the yet-to-be-released marker-assisted breeding chickpea lines which are currently under evaluation – caught the eye of George Birigwa, Senior Programme Officer at the Program for Africa’s Seed Systems (PASS) initiative of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), which is now supporting the work being undertaken by Paul and his team through the Egerton Seed Unit and Variety Development Centre (of which Paul is currently Director) at the Agro-Based Science Park.

Yet whilst Paul’s love affair with chickpeas has evidently been going from strength to strength, he has also enjoyed a healthy courtship with research in other legumes: by engaging in a Pan-African Bean Research Alliance (PABRA) bean project coordinated by the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), Paul and his team were able to release and commercialise three bean varieties which are currently in farmers’ fields in Kenya.

With so many pots on the boil, the heat is certainly on in Paul’s research kitchen, yet he continues to navigate such daily challenges with characteristic aplomb. As a proven leader of change in his community and a ‘ can-do, make-it-happen’ kind of guy, he is driving research forward to ensure that both his school and discipline remain fresh and relevant – and he’s taking his colleagues, students and local community along with him every step of the way.

Indeed, rallying the troops for the greater good is an achievement he values dearly: “By coming together, pooling skills from biotechnology, agronomy, breeding, statistics and other disciplines, we are stronger as a unit and better equipped to offer solutions to African agriculture and to the current challenges we face,” he affirms. This is a crusade he has no plans to abandon any time soon, as revealed when quizzed on his future aspirations and career plans: “My aim is to continue nurturing my current achievements, and to work harder to improve my abilities and provide opportunities for my institution, colleagues, students, friends and people within the region.”

With the chickpea research community thriving, resulting in concrete food-security alternatives, we raise a toast to Paul Kimurto and his chickpea champions!

Links

- Chickpeas – Project | Blogposts | Videos | Slides | InfoCentre

- PHOTOS: An album on Flickr with photos from a GCP visit to Paul’s team at Egerton University

- Paul’s slides on the data management of his research below