“Having funding to support PhD students and provide them with the resources they need to complete their research is very fulfilling and will go a long way to enhance the long-term success of our goal: to provide Kenyan farmers with cereal varieties that will improve their yields and make their livelihood more secure and sustainable.” – Samuel Gudu, Professor and Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Planning & Development) at Moi University, and now Principal, Rongo University College: a Constituent College of Moi University, Kenya.

Growing up, and getting dirty

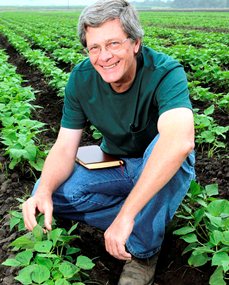

Learner, teacher and leader. Sam Gudu has been all these, but this doesn’t mean he doesn’t like to get his hands dirty.

Growing up in a small fishing village on the banks of Lake Victoria, in Western Kenya, Sam was always helping his parents to fish and garden, or his grandparents to muster cattle.

“I remember spending long hours before and after school either on the lake or in the field helping to catch, harvest and produce enough food to eat and support our family,” reminisces Sam.

He attributes this “hard and honest” work to why he still enjoys being in the field.

“Even though I now spend most of my days doing administration work, I’m always trying to get out into the field to get my hands dirty and see how our research is helping to make the lives of Kenyan farmers a lot more profitable and sustainable,” he says.

I was… captivated by the study of genetics as it focused on what controlled life.”

Taking control: bonded to genetics, at home and away

Sam says his love for the land transferred to an interest and then passion in the classroom during high school. “I became very interested in Biology as I wanted to know how nature worked,” says Sam. “I was particularly captivated by the study of genetics as it focused on what controlled life.”

This interest grew during his undergraduate years at the University of Nairobi where he completed a Bachelor of Science in Agriculture and a Master’s of Science in Agriculture, focusing on genetics and plant breeding.

“I fondly remember a lecturer during my master’s degree studies who would continually give us challenges to test in the field and in the lab. If you had a viable idea he supported you to design an experiment to test your theory. I like to use the same method in teaching my students. I discuss quite a lot with my students and I encourage them to disagree if they use scientific process.”

Driven by an ever-growing passion and enthusiasm, Sam secured a scholarship to travel to Canada to undertake a PhD in Plant Genetics and Biotechnology at the University of Guelph.

[There has been an] influx of young Kenyans who are choosing degrees in science. The Kenyan Government has recently increased its funding for science and research…”

Nurturing the next breed of geneticists

After graduating from Guelph in 1993, Sam returned to Kenya to lecture at Moi University where he initiated and helped expand teaching and research in the disciplines of Genetic Engineering, Biotechnology and Molecular Biology.

In the past two decades, he has recruited young talented graduates in genetics and helped acquire advanced laboratory equipment that has enabled practical teaching and research in molecular biology.

“I wouldn’t be where I am now were it not for all the assistance I received from my teachers, lecturers and supervisors; notably my PhD supervisor – Prof Ken Kasha of the University of Guelph. So I’ve always tried my best to give the same assistance to my students. It’s been hard work but very rewarding, especially when you see your students graduate to become peers and colleagues.” (Meet some of Sam’s students)

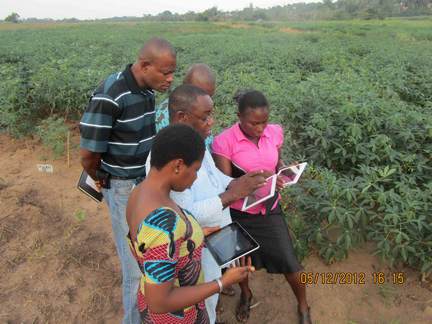

Sam (2nd right), with some of his young charges: Thomas Matonyei (far left), Edward Saina (2nd left) and Evans Ouma (far right).

Sam is particularly buoyed by the influx of young Kenyans who are choosing degrees in science.

“The Kenyan Government has recently increased its funding for science and research to two percent of GDP,” explains Sam. “This has not only helped us compete in the world of research but has helped raise the profile of science as a career.”

Knowing which genes are responsible for aluminium tolerance will allow us to more precisely select for aluminium tolerance in our breeding programmes, reducing the time it takes for us to breed varieties that will have improved yields in acidic soils without the use of costly inputs such as lime or fertiliser.” (See the work that Sam does in this area with other partners outside Kenya)

So far we have produced 10 inbred lines that are outstanding for phosphorus efficiency, and two that were outstanding for aluminium toxicity. We are now testing unique verities developed for acid soils of Kenya.”

Slashing costs, increasing yields and resilience: genes to the rescue

Currently, Sam and his team of young researchers at Moi University are working with several other research facilities around the world (Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation, EMBRAPA; Cornell University, USA; the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI); Japan’s International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences, JIRCAS; and the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute, KARI–Kitale) to develop high-yielding maize varieties adapted to acid soils in East Africa, using molecular and conventional breeding approaches.

Can you spot Sam? It’s a dual life. Here, he sheds his field clothes in this 2011 suit-and-tie moment with Moi University and other colleagues involved in the projects he leads. Left to right: P Kisinyo, J Agalo, V Mugalavai, B Were, D Ligeyo, S Gudu, R Okalebo and A Onkware.

Acid soils cover almost 13 per cent of arable land in Kenya, and most of the maize-growing areas in Kenya. In most of these areas, maize yields are reduced by almost 60 per cent. Aluminium toxicity is partly responsible for the low and declining yields.

“We found that most local maize varieties and landraces grown in acid soils are sensitive to aluminium toxicity. The aluminium reduces root growth and as such the plant cannot efficiently tap into native soil phosphorus, or even added phosphorus fertiliser. However, there are some varieties of maize that are suited to the conditions even if you don’t use lime to improve the soil’s pH. So far we have produced 10 inbred lines that are outstanding for phosphorus efficiency, and two that were outstanding for aluminium toxicity. We are now testing unique varieties developed for acid soils of Kenya.”

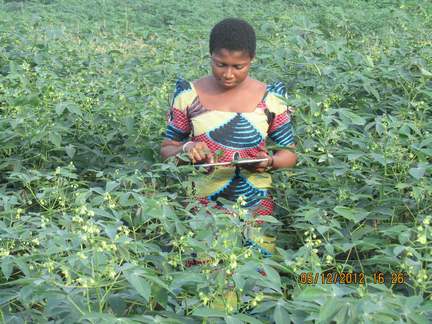

Sam (left) addressing a mixed group of farmers and researchers at Sega, Western Kenya, in June 2009.

In a related project, Sam is working with the same partners to understand the molecular and genetic basis for aluminium tolerance.

“Knowing which genes are responsible for aluminium tolerance will allow us to more precisely select for aluminium tolerance in our breeding programmes, reducing the time it takes for us to breed varieties that will have improved yields in acidic soils without the use of costly inputs such as lime or fertiliser.”

… my greatest achievements thus far have been those which have benefited farmers and my students.”

Summing up success

For Sam, the greatest two successes in his career have not been personal.

“If I’m honest, I have to say my greatest achievements thus far have been those which have benefited farmers and my students. Having funding to support PhD students and provide them with the resources they need to complete their research is very fulfilling and will go a long way to enhance the long-term success of our goal: to provide Kenyan farmers with cereal varieties that will improve their yields and make their livelihoods more secure and sustainable.”

With a dozen aluminium-tolerant and phosphorus-efficient breeding lines under their belt already, and two lines submitted for National Variety Trials (a pre-requisite step to registration and release to farmers), Sam and his team seem well on their way towards their goal, and we wish them well in their quest and labour.

Links:

- PHOTOS:

- The project Sam leads

- BLOG: Sam’s work with other partners

- Comparative Genomics (cereals) Research Initiative | InfoCentre

- Media coverage: Sorghum and food security in Kenya

- InfoCentres – Maize| Sorghum