Triumphs and tragedies, pitfalls and potential of the ‘camel crop’

We travel through space and time, with a pair of researchers who have a pronounced passion for a plant brought to Africa by seafaring Portuguese traders in the 16th century. Fastforwarding to today, half a millennium later, the plant is widespread and deep inland, and is the staple food for Africa’s most populous nation – Nigeria.

Meet cassava, the survivor. After rice and maize, cassava is the third-largest source of carbohydrate in the tropics. Surviving, nay thriving, in poor soils and shaking off the vagaries of weather – including an exceptionally high threshold for drought – little wonder that cassava, the ‘camel’ of crops is naturally the main staple in Nigeria. And with that, it has propelled Nigeria to the very top of the cassava totem pole as the world’s leading cassava producer, and consumer: most Nigerians eat cassava in one form or another practically every day.

Great, huh? But there’s also a darker side to cassava, as we will soon find out from our two cassava experts. For starters, the undisputed global cassava giant, Nigeria, produces just enough to feed herself. Even if there were a surplus for the external demand, farming families, which make up 70 percent of the Nigerian population, have limited access to these lucrative external markets. Secondly, cassava mosaic disease (CMD) and cassava brown streak disease (CBSD) are deadly in Africa. Plus, cassava is a late bloomer (up to two years growth cycle, typically one year), so breeding and testing improved varieties takes time. Finally, cassava is most definitely not à la mode at all in modern crop breeding: the crop is an unfashionably late entrant into the world of molecular breeding, owing to its complex genetics which denied cassava the molecular tools that open the door to this glamour world of ‘crop supermodels’.

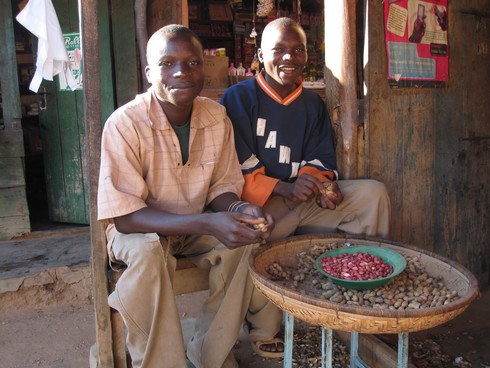

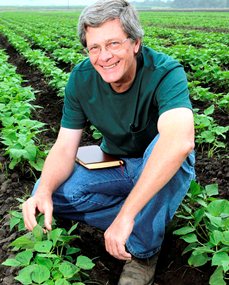

But all is not doom and gloom, which inexorably dissolve in the face of dogged determination. All the above notwithstanding, cassava’s green revolution seems to be decidedly on the way in Nigeria, ably led by born-and-bred sons of the soil: Chiedozie Egesi and Emmanuel Okogbenin (pictured right) are plant breeders and geneticists at the National Root Crops Research Institute (NRCRI). With 36 years’ collective cassava research experience between them, the two men are passionate about getting the best out of Nigeria’s main staple crop, and getting their hands into the sod while about it: “I’m a plant breeder,” says Chiedozie, with pride. “I don’t just work in a laboratory. I am also in the field to experience the realities.”

Hitting two birds with one stone…two stones are even better!

As Principal Investigators (PIs) leading three different projects in the GCP-funded Cassava Research Initiative, Chiedozie and Emmanuel, together with other colleagues from across Africa, form a formidable team. They also share a vision to enable farmers increase cassava production for cash, beyond subsistence. This means ensuring farmers have new varieties of cassava that guarantee high starch-rich yields in the face of evolving diseases and capricious weather.

Chiedozie is one of cassava’s biggest fans. His affection for, and connection to, cassava is almost personal and definitely paternal. He is determined to deploy the best plant-breeding techniques to not only enhance cassava’s commercial value, but to also protect the crop against future disease outbreaks, including ‘defensive‘ breading. But more on that later…

Emmanuel is equally committed to the cassava cause. As part of his brief, Emmanuel liaises with the Nigerian government, to develop for – and promote to – farmers high-starch cassava varieties. This ensures a carefully crafted multi-pronged strategy to revolutionise cassava: NRCRI develops and releases improved varieties, buttressed by financial incentives and marketing opportunities that encourage farmers to grow and sell more cassava, which spurs production, thereby simultaneously boosting food security while also improving livelihoods.

Standing tall. Disease resistance and high starch and yield aside, farmers also prefer an upright architecture, which not only significantly increases the number of plants per unit, but also favours intercropping, a perennial favourite for cassava farmers.

Cross-continental crosses and cousins, magic for making time, and clocking a first for cassava

No one has been able to manufacture time yet, so how can breeders get around cassava’s notoriously long breeding cycle? MAS (marker-assisted selection) is crop breeding’s magic key for making time. And just as humans can benefit from healthy donor organ replacement, so too does cassava, with cross-continental cousins donating genes to rescue the cousin in need. Latin American cassava is nutrient-rich, while African cassava is hardier, being more resilient to pests, disease and harsh environments.

Thanks to marker-assisted breeding, CMD resistance from African cassava can now be rapidly ‘injected’ much faster into Latin American cassava for release in Africa. Consequently, in just a three-year span (2010–2012), Chiedozie, Emmanuel, Martin Fregene of the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center (USA) and the NRCRI team, released two new cassava varieties from Latin American genetic backgrounds (CR41-10 and CR36-5). These varieties, developed with GCP funding, are the first molecular-bred cassava ever to be released, meaning they are a momentous milestone in cassava’s belated but steady march towards its own green revolution.

Marker-assisted selection is much cheaper, and more focused.”

On the cusp of a collaborative cassava revolution: on your marks…

With GCP funding, Chiedozie and Emmanuel have been able to use the latest molecular-breeding techniques to speed up CMD resistance. Using marker-assisted selection (MAS) which is much more efficient, the scientists identified plants combining CMD resistance with desirable genetic traits.

“MAS for CMD resistance from Latin American germplasm is much cheaper, and more focused,” explains Emmanuel. “There is no longer any need to ship in tonnes of plant material to Africa. We can narrow down our search at an early stage by selecting only material that displays markers for the genetic traits we’re looking for.” Using markers, combining traits (known as ‘gene pyramiding’) for CMD resistance is faster and more efficient, as it is difficult to distinguish phenotypes with multiple resistance in the field by just observing with the naked eye. This is what makes marker-assisted breeding so effective and desirable in Africa.

GCP’s mode of doing business coupled with its community spirit has spurred the NRCRI scientists to cast their eyes further out to the wider horizon beyond their own borders.

By collaborating with research centres in other parts of the world, Emmanuel and Chiedozie have made remarkable strides in cassava breeding. According to Emmanuel, “GCP helped us make links with advanced laboratories and service providers like LGC Genomics. The outsourcing of genotyping activities for molecular breeding initiatives is very significant, as it enables us to carry out analyses not otherwise possible.”

We can’t afford to sit idle until it comes – we need to be armed and on the ready.”

‘Defensive’ breeding: partnerships to pre-empt catastrophe and combat disease

Closer home in Africa, as PI of the corollary African breeders community of practice (CoP) project, Emmanuel co-organises regular workshops with plant breeders from a dozen other countries (Côte d’Ivoire, DR Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda and South Sudan). These events are an opportunity to share knowledge on molecular breeding and compare notes.

Of the diseases that afflict cassava, CBSD is the most devastating. Mercifully, in Nigeria, the disease is non-existent, but Chiedozie is emphatic that this is by no means cause for complacency. “If CBSD gets to Nigeria, it would be a monumental catastrophe!” he cautions. “We can’t afford to sit idle until it comes – we need to be armed and on the ready.”

Putting words to action, though this work on CBSD resistance is still in its early stages, more than 1,000 cassava genotypes (different genetic combinations) have already have been screened in the course of just one year. Chiedozie hopes that the team will be able to identify key genetic markers, and validate these in field trials in Tanzania, where CBSD is widespread. This East African stopover, Chiedozie emphasises, is a crucial checkpoint in the West African process. So the cassava CoP not only provides moral but also material support.

And Africa is not the limit. GCP-funded work on CMD resistance is more advanced than the CBSD work, though the real breakthrough in CMD only happened recently, on the international arena within which the African breeders now operate. According to Chiedozie, two entire decades of screening cassava genotypes from Latin America yielded no resistance to CMD. The reason for this is that although it is widespread in Africa, CMD is non-existent in Latin America.

Through international collaborative efforts, cassava scientists, led by Martin Fregene (now based in USA), screened plants from Nigeria and discovered markers for the CMD2 gene, indicating resistance to CMD. Once they had found these markers, the scientists were off and away! By taking the best of the Latin American material and crossing it with Nigerian genotypes that have CMD resistance, promising lines were developed from which the Nigerian team produced two new varieties. These varieties, CR41-10 and CR36-5, have already been released to farmers, and that is not all. More varieties bred using these two as parents are in the pipeline.

“GCP funding has given us the opportunity to show that a national organisation can do the job and deliver.”

Delivery attracts

The success of the CGP-funded cassava research in Nigeria lies in its in-country leadership. Chiedozie, Emmanuel and Martin are native Nigerian scientists and as such are – in many ways – best placed to drive a research collaboration to benefit the country’s farmers and boost food security. “GCP funding has given us the opportunity to show that a national organisation can do the job and deliver,” says Chiedozie.

This proven expertise has helped NRCRI forge other partnerships and attract more financial support, for example from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for a project on genomic selection. GCP support has also bolstered communications with the Nigerian government, which has launched financial instruments, such as a wheat tariff,* to boost cassava production and use.

[Editors note: * wheat tariff: The Nigerian government is trying to reduce wheat import bills and also boost cassava commercialisation by promoting 20 percent wheat substitution in bread-making. Tariffs are being imposed on wheat to dissuade heavy imports and encourage utilisation of high-quality cassava flour for bread.]

“The government feels that to quickly change the fortunes of farmers, cassava is the way to go,” explains Emmanuel. He clarifies, “The tariff from wheat is expected to be ploughed back to support agricultural development – especially the cassava sector – as the government seeks to increase cassava production to support flour mills. Cassava offers a huge opportunity to transform the agricultural economy and stimulate rural development, including rapid creation of employment for youth.”

The Nigerian government is right in step aiding cassava’s march towards the crop’s own green revolution, as is evident in the the Minister of Agriculture’s tweet earlier this year, and in his video interview below. See also related media story, ‘Long wait for cassava bread’.

Clearly, the ‘camel’ crop – once considered an ‘orphan’ in research – has travelled as far in science as in geography, and it is a precious asset to deploy for food production in a climate-change-prone world. As Emmanuel observes, cassava’s future can only be brighter!

Slides by Chiedozie and Emmanuel

More links

- Chiedozie’s profile

- Cassava – Research | Community of practice | InfoCentre | Podcasts | Videos | Data management | Blogposts |Slides

- Integrated Breeding Platform (IBP)