For this ‘IBP story-telling season’, our next stop is very fittingly Africa, and her most populous nation, Nigeria. Travel with us!

Having already heard the Integrated Breeding Platform (IBP) story on data from Arllet (spiced with a brief detour through Asia’s sun-splashed rice paddies), and on IBP’s Breeding Management System from Mark (where we perched on a corner on his Toulouse workbench of tools and data), we next set out to get an external narrative on IBP, and specifically, one from an IBP user. Well, we got more than we had bargained for from our African safari…

Yemi Olojede (pictured) is much more than a standard IBP user. An agronomist by training with a couple of decades-plus experience, he not only works closely with breeders and other crop scientitsts, but is also a research coordinator and data manager. As you can imagine, this made for a rich and insightful conversation, ferrying us far beyond the frontiers of Yemi’s base in Nigeria, to the rest of West Africa, further out to Africa , and as far afield as Mexico, in his travels and travails with partners. We now bring to you some of this captivating conversation…

Yemi has been working for the last 23 years (since 1991) at Nigeria’s National Root Crops Research Institute (NRCRI) at Umudike in various capacities. After heading NRCRI’s Minor Root Crops Programme for 13 years, he was last year appointed Coordinator-in-Charge of the Cassava Research Programme.

But his involvement in agriculture goes much further back than NRCRI: Yemi says he “was born into farming”. His father, to whom he credits his love for agriculture, was a cocoa farmer. “I enjoy seeing things grow. When I see a field of crops …what a view!” Yemi declares.

Yemi is also the Crop Database Manager for NRCRI’s GCP-funded projects. He spent time at GCP headquarters in Mexico in February 2012 to sharpen his skills and provide user insights to the IBP team on the cassava database, on the then nascent Integrated Breeding Fieldbook, and on the tablet that GCP was considering for electronic field data collection and management.

To meet the farmers’ growing need for improved higher-yielding and stress-tolerant varieties, plant breeders are starting to incorporate molecular-breeding techniques to speed up conventional breeding.

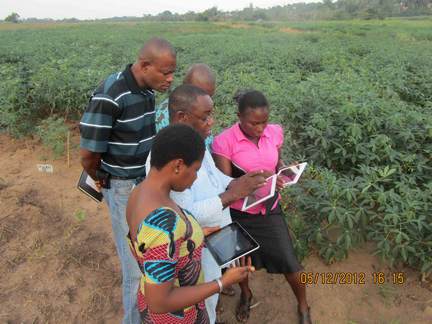

Flashback to 2010: GCP was then piloting and testing small handheld devices for data collection. Field staff going through a training session for these under Yemi’s watchful eye (right).

But for this to happen effectively, cassava breeders require consistent and precise means to collect and upload research and breeding data, and secure facilities to upload that data into the requisite databases and share it with their peers. Eighty percent of farmers in Africa have less than a hectare of land – that’s roughly two football fields! With so little space, they need high-value crops that consistently provide them with viable yields, particularly during drought. For this reason, an increasing number of Nigerian farmers are adopting cassava. It is not as profitable as, say, wheat, but it has the advantage of being less risky. The Nigerian government is encouraging this change and is implementing a Cassava Transformation Agenda, which will improve cassava markets and value chains locally and create a sustainable export market. All this is designed to encourage farmers to grow more cassava.

Enter GCP’s Integrated Breeding Platform (IBP), which has been working closely with NRCRI and other national breeding programmes to develop the right informatic tools and support services for the job. The International Cassava Information System (ICASS), the Integrated Breeding Fieldbook and the tablet are all part of the solution, backed up by a variety of bioinformatic tools for data management, data analysis and breeding decision support that have been developed to meet the specific needs of the users.

I enjoy working with the team. They pay attention to what we as breeders want and are determined to resolve the issues we raise”

Fastfoward to 2012: Based on feedback, a larger electronic tablet was favoured over the smaller handheld device. Yemi (centre) takes field staff through the paces in tablet use.

The database and IB Fieldbook

“When I received the tablet I was excited! I had heard so much about it but only contributed ideas for its use through Skype and email,” Yemi remembers, echoing a sentiment that is frequently expressed by many partners who have been introduced to the device. “I experimented with the Integrated Breeding Fieldbook software focusing on pedigree management, trait ontology management, template design ‒ testing how easy it was to input data into the program and database.” Yemi noted a few problems with layout and data uploading and suggested a number of additional features. The IBP Team found these insights particularly useful and worked hard to implement them in time for the 2nd Scientific Conference of the Global Cassava Partnership for the 21st Century (GCP21 II), held in Kampala, Uganda, in June, 2012.

“I enjoy working with the team. They pay attention to what we as breeders want and are determined to resolve the issues we raise,” says Yemi. He believes the IB FieldBook and the tablet, on which it runs, will greatly benefit breeders all over the world, but particularly in Africa. “At the moment, our breeders and researchers have to write down their observations in a paper field book, take that book back to their computer, and enter the data into an Excel spreadsheet,” he notes. “We have to double-handle the data and this increases the possibility of mistakes, especially when we are transferring it to our computers. The IB Fieldbook will streamline this process, minimising the risk of making mistakes, as we enter our observations straight into the tablet, using specified terms and parameters, which will upload all the data to the shared central database when it’s connected to the internet.”

The whole room was wide-eyed and excited when they first saw the tablets”

Bringing the tablet to Africa

After his trip to Mexico, Yemi was concerned that some African breeders would be put off using the IB Fieldbook and accompanying electronic tablet because both require some experience with computers. “I found the tablet and the FieldBook quite easy to use because I’m relatively comfortable with computers,” says Yemi. “The program is very similar to MS-Excel, which many breeders are comfortable with, but I still thought it would be difficult to introduce it given that computer literacy across the continent is very uneven.”

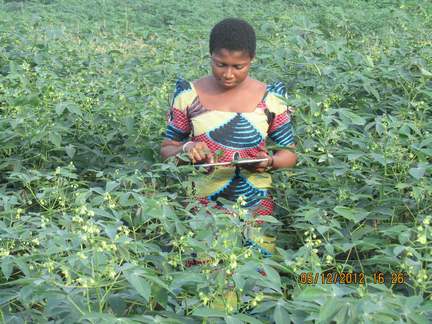

Slim, elegant, portable and nearly invisible is this versatile tool. A junior scientist at NRCRI Umudike tries out the tablet during the 2012 training session.

At the GCP21 II meeting in Uganda, Yemi helped the IBP team run IB Fieldbook workshops for plant breeders from developing countries, with an emphasis on data quality and sharing. “The whole room was wide-eyed and excited when they first saw the tablets. They initially had trouble using them and I thought it was going to be a very difficult workshop, but by the end they all felt confident enough to use them by themselves and were sad to have to give them back!”

They … go back to their research institutes and train their colleagues, who are more likely to listen and learn from them than from someone else.”

Providing extra support, cultivating trust

Yemi recounts that attendees were particularly pleased when they received a step-by-step ‘how-to’ manual to help them train other breeders in their institutes, with additional support to be provided by the IBP or Yemi’s team in Nigeria. “They were worried about post-training support,” says Yemi. “We told them if they had any challenges, they could call us and we would help them. I feel this extra support is a good thing for the future of this project, as it will build confidence in the people we teach. They can then go back to their research institutes and train their colleagues, who are more likely to listen and learn from them than from someone else.”

In developing nations, it is important that we share data, because we don’t all have the capacity to carry out molecular breeding at this time, and data sharing would facilitate the dissemination of the benefits to a wider group”

Sharing data to utilise molecular breeding

Yemi asserts that incorporating elements of molecular breeding has helped NRCRI a great deal. With conventional breeding, it would take six to 10 years to develop a variety before release, but with integrated breeding (conventional breeding that incorporates molecular breeding elements) it is possible to develop and release new varieties in three to four years ‒ half the time. Farmers would hence be getting new varieties of cassava that will yield 20‒30 percent more than the lines they are currently using in a much shorter time.

“In developing nations, it is important that we share data, because we don’t all have the capacity to carry out molecular breeding at this time, and data sharing would facilitate the dissemination of the benefits to a wider group,” says Yemi. “I enjoy helping people with this technology because I know how much it will make their job easier.”

Links

- ‘Dosing’ the digital divide: a tablet for that field-to-desk headache

- Integrated Breeding Platform

- Cassava breeders community of practice

- Cassava InfoCentre

- Cultivating a culture of change – Tools and tips for ‘SHARP’ data management, in and for the Information Age

- A new breed of Workbench – Introducing the Breeding Management System

- Cassava’s gain, and surgery’s ‘pain’: Career crossings and causerie with Chiedozie Egesi