DNA spiral

Crop researchers including plant breeders across five continents are collaborating on several GCP projects to develop local varieties of sorghum, maize and rice, which can withstand phosphorus deficiency and aluminium toxicity – two of the most widespread constraints leading to poor crop productivity in acidic soils. These soils account for nearly half the world’s arable soils, with the problem particularly pronounced in the tropics, where few smallholder farmers can afford the costly farm inputs to mitigate the problems. Fortunately, science has a solution, working with nature and the plants’ own defences, and capitalising on cereal ‘family history’ from 65 million years ago. Read on in this riveting story related by scientists, that will carry you from USA to Africa and Asia with a critical stopover in Brazil and back again, so ….

… welcome to Brazil, where there is more going than the 2014 football World Cup! Turning from sports to matters cerebral and science, drive six hours northwest from Rio de Janeiro and you’ll arrive in Sete Lagoas, nerve centre of the EMBRAPA Maize and Sorghum Research Centre. EMBRAPA stands for Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária ‒ in English, the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation.

Jurandir Magalhães

Jurandir Magalhães (pictured), or Jura as he prefers to be called, is a cereal molecular geneticist and principal scientist who’s been at EMBRAPA since 2002.

“EMBRAPA develops projects and research to produce, adapt and diffuse knowledge and technologies in maize and sorghum production by the efficient and rational use of natural resources,” Jura explains.

Such business is also GCP’s bread and butter. So when in 2004, Jura and his former PhD supervisor at Cornell University, Leon Kochian, submitted their first GCP project proposal to clone a major aluminium tolerance gene in sorghum they had been searching for, GCP approved the proposal.

“We were already in the process of cloning the AltSB gene,” remembers Jura, “So when this opportunity came along from GCP, we thought it would provide us with the appropriate conditions to carry this out and complete the work.”

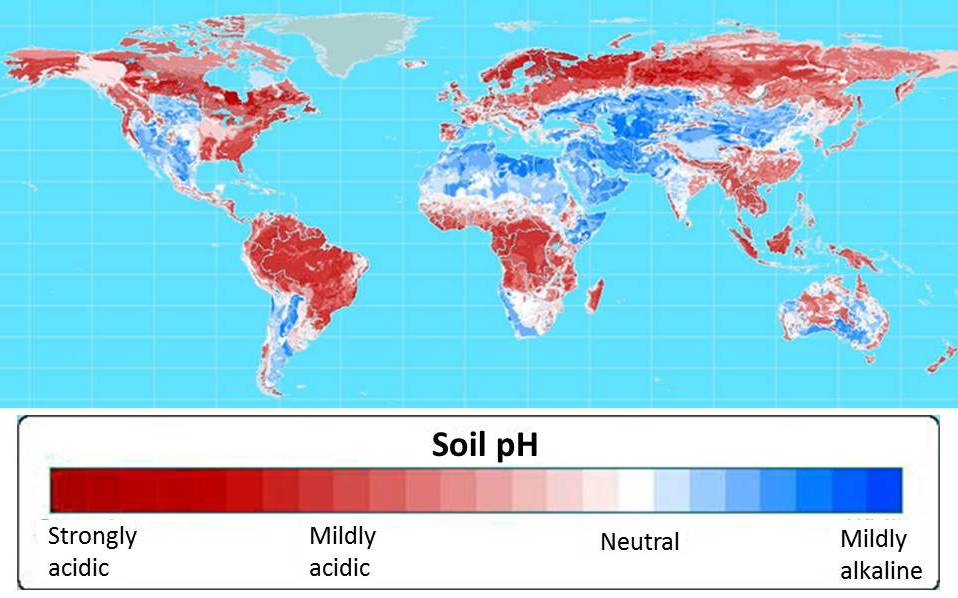

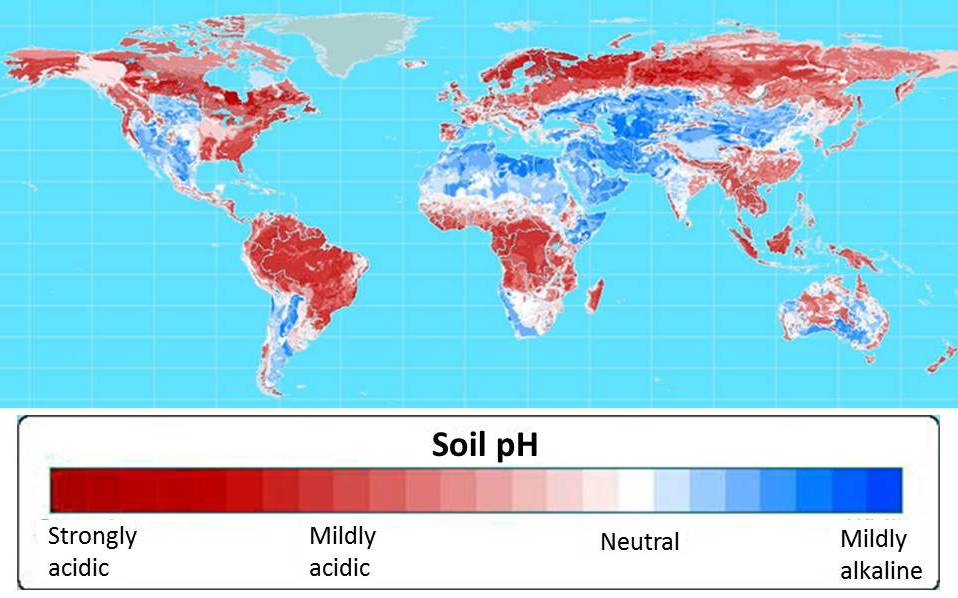

Cloning the AltSB gene would prove to be one of the first steps in GCP’s foundation sorghum and maize projects, both of which seek to provide farmers in the developing world with crops that will not only survive but thrive in the acidic soils that make up more than half of the world’s arable soils (see map below).

More than half of world’s potentially arable soils are highly acidic.

… identifying the AltSB gene was a significant achievement which brought the project closer to their final objective, which is to breed aluminium-tolerant crops that will improve yields in harsh environments, in turn improving the quality of life for farmers.”

A star is born: identifying and cloning AltSB

For 30 years, Leon Kochian (pictured below) has combined lecturing and supervising duties at Cornell University and the United States Department of Agriculture, with his quest to understand the genetic and physiological mechanisms behind the ability of some cereals to withstand acidic soils. Leon is also the Product Delivery Coordinator for GCP’s Comparative Genomics Research Initiative.

Leon Kochian

Aluminium toxicity is associated with acidic soils and is the primary limitation on crop production for more than 30 percent of farmland in Southeast Asia and Latin America, and approximately 20 percent in East Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and North America. Aluminium ions damage roots and impair their growth and function. This results in reduced nutrient and water uptake, which in turn depresses yield.

“These effects can be limited by applying lime to increase the soil’s pH. However, this isn’t a viable option for farmers in developing countries,” says Leon, who was the Principal Investigator for the premier AltSB project and is currently involved in several off-shoot projects.

Working on the understanding that grasses like barley and wheat use membrane transporters to insulate themselves against subsoil aluminium, Leon and Jura searched for a similar transporter in sorghum varieties that were known to tolerate aluminium.

“In wheat, when aluminium levels are high, these membrane transporters prompt organic acid release from the tip of the root,” explains Leon. “The organic acid binds with the aluminium ion, preventing it from entering the root. We found that in certain sorghum varieties, AltSB is the gene that encodes a specialised organic acid transport protein – SbMATE* – which mediates the release of citric acid. From cloning the gene, we found it is highly expressed in aluminium-tolerant sorghum varieties. We also found that the expression increases the longer the plant is exposed to high levels of aluminium.”

[*Editor’s note: different from the gene with the same name, hence not in italics]

Leon says identifying the AltSB gene and then cloning it was a significant achievement and it brought the project closer to their final objective, which he says is “to breed aluminium-tolerant crops that will improve yields in harsh environments, in turn improving the quality of life for farmers.”

This research was long and intensive, but it set a firm foundation for the work in GCP Phase II, which seeks to use what we have learnt in the laboratory and apply it to breed crops that are tolerant to biotic or abiotic stress such as aluminium toxicity and phosphorus deficiency.”

Comparative genomics: finding similar genes in different crops

Wheat, maize, sorghum and rice are all part of the Poaceae (grasses) family, evolving from a common grass ancestor 65 million years ago. Over this time they have become very different from each other. However, at a genetic level they still have a lot in common.

Over the last 20 years, genetic researchers all over the world have been mapping these cereals’ genomes. These maps are now being used by geneticists and plant breeders to identify similarities and differences between the genes of different cereal species. This process is termed comparative genomics and is a fundamental research theme for GCP research as part of its second phase.

Rajeev Varshney

“The objective during GCP Phase I was to study the genomes of important crops and identify genes conferring resistance or tolerance to biotic or abiotic stresses,” says Rajeev Varshney (pictured), Director, Center of Excellence in Genomics and Principal Scientist in applied genomics at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT). “This research was long and intensive, but it set a firm foundation for the work in GCP Phase II, which seeks to use what we have learnt in the laboratory and apply it to breed crops that are tolerant to biotic or abiotic stress such as aluminium toxicity and phosphorus deficiency.”

Until August 2013, Rajeev had oversight on GCP’s comparative genomics research projects on aluminium tolerance and phosphorus deficiency is sorghum, maize and rice, as part of his GCP role as Leader of the Comparative and Applied Genomics Theme.

“Phosphorus deficiency and aluminium toxicity are soil problems that typically coincide in acidic soils,” says Rajeev. “They are two of the most critical constraints responsible for low crop productivity on acid soils worldwide. These projects are combining the aluminium tolerance work done by EMBRAPA and Cornell University with the phosphorus efficiency work done by IRRI [International Rice Research Institute] and JIRCAS [Japan International Research Centre for Agricultural Sciences] to first identify and validate similar aluminium-tolerance and phosphorus-efficient genes in sorghum, maize and rice, and then, secondly, breed crops with these combined improvements.”

These collaborations are really exciting! They make it possible to answer questions that we could not answer ourselves, or that we would have overlooked, were it not for the partnerships.”

When AltSB met Pup1…

Having spent more than a decade identifying and cloning AltSB, Jura and Leon have recently turned their attention to identifying and cloning the genes responsible for phosphorus efficiency in sorghum. Luckily, they weren’t starting from scratch this time, as another GCP project on the other side of the world was well on the way to identifying a phosphorus-efficiency gene in rice.

Led by Matthias Wissuwa at JIRCAS and Sigrid Heuer at IRRI, the Asian base GCP project had identified a gene locus, which encoded a particular protein kinase that allowed varieties with this gene to grow successfully in low-phosphorous conditions. They termed the region of the rice genome where this gene resides as ‘phosphorus uptake 1’ or Pup1 as it is commonly referred to in short.

“In phosphorus-poor soils, this protein kinase instructs the plant to grow larger, longer roots, which are able to forage through more soil to absorb and store more nutrients,” explains Sigrid. “By having a larger root surface area, plants can explore a greater area in the soil and find more phosphorus than usual. It’s like having a larger sponge to absorb more water!”

Read more about the mechanics of Pup-1 and the evolution of the project.

Jura and Leon are working on the same theory as IRRI and JIRCAS, that larger and longer roots enhance phosphorus efficiency. They are identifying sorghum with these traits, using comparative genomics to identify a locus similar to Pup1 in these low-phosphorus-tolerant varieties, and then verify whether the genes at this locus are responsible for the trait.

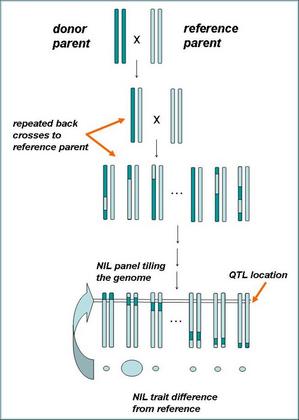

“So far, the results are promising and we have evidence that Pup1 homologues may underlie a major QTL for phosphorous uptake in sorghum,” says Jura who is leading the project to identify and validate Pup1 and other phosphorus-efficiency QTLs in sorghum. QTL stands for ‘quantitative trait locus’ which refers to stretches of DNA containing ‒ or linked to ‒ the genes responsible for a quantitative trait “What we have to do now is to see if this carries over in the field, leading to enhanced phosphorus uptake and grain yield in low-phosphorus soils,” he adds.

Jura and Leon are also returning the favour to IRRI and JIRCAS and are collaborating with both institutes to identify and clone in rice similar genes to the AltSB gene in sorghum.

“These collaborations are really exciting! They make it possible to answer questions that we could not answer ourselves, or that we would have overlooked, were it not for the partnerships,” says Sigrid.

To make a difference in rural development, to truly contribute to improved food security through crop improvement and incomes for poor farmers, we knew that capacity development had to be a continuing cornerstone in our strategy.”

Building capacity in Africa

In GCP Phase II which is more application oriented, projects must have objectives that deliver products and build capacity in developing-world breeding programmes.

Jean-Marcel Ribaut

“The thought behind the latter requirement is that GCP is not going to be around after 2014 so we need to facilitate these country breeding programmes to take ownership of the science and products so they can continue it locally,” says Jean-Marcel Ribaut, GCP Director (pictured). “To make a difference in rural development, to truly contribute to improved food security through crop improvement and incomes for poor farmers, we knew that capacity development had to be a continuing cornerstone in our strategy.”

Back to Brazil: Jura says this requirement is not uncommon for EMBRAPA projects as the Brazilian government seeks to become a world leader in science and agriculture. “Before GCP started, we had been working with African partners for five to six years through the McKnight Project. It was great when GCP came along as we were able to continue these collaborations.”

Samuel Gudu

One collaboration Jura was most pleased to continue was with his colleague and friend, Sam Gudu (pictured), from Moi University, Kenya. Sam has been collaborating with Jura and Leon on several GCP projects and is the only African Principal Investigator in the Comparative Genomics Research Initiative.

“Our relationship with EMBRAPA and Cornell University has been very fruitful,” says Sam. “We wouldn’t have been able to do as much as we have done without these collaborations or without our other international collaborators at IRRI, JIRCAS, ICRISAT or Niger’s National Institute of Agricultural Research [INRAN].”

Sam is currently working on several projects with these partners looking at validating the genes underlying major aluminium-tolerance and phosphorus-efficiency traits in local sorghum and maize varieties in Kenya, as well as establishing a molecular breeding programme.

“The molecular-marker work has been very interesting. We have selected the best phosphorus-efficient lines from Brazil and Kenya, and have crossed them with local varieties to produce several really good hybrids which we are currently field-testing in Kenya,” explains Sam. “Learning and using these new breeding techniques will enable us to select for and breed new varieties faster.”

Sam is also grateful to both EMBRAPA and Cornell University for hosting several PhD students as part of the project. “This has been a significant outcome as these PhD students are returning to Kenya with a far greater understanding of molecular breeding which they are sharing with us to advance our national breeding programme.”

We’ve used the knowledge that Jura’s and Leon’s AltSB projects have produced to discover and validate similar genes in maize…We identified Kenyan lines carrying the superior allele of ZmMATE …This work will also improve our understanding of what other mechanisms may be working in the Brazilian lines too.”

‘Everyone’ benefits! Applying the AltSB gene to maize

Claudia Guimarães (pictured) is a maize geneticist at EMBRAPA. But unlike Jura, her interest lies in maize.

Claudia Guimarães

Working on the same comparative genomics principle used to identify Pup1 in sorghum, Claudia has been leading a GCP project replicating the sorghum aluminium tolerance work in maize.

“We’ve used the knowledge that Jura’s and Leon’s AltSBprojects have produced to discover and validate similar genes in maize,” explains Claudia. “From our mapping work we identified ZmMATE as the gene underlying a major aluminium tolerance QTL in maize. It has a similar sequence as the gene found in sorghum and it encodes a similar protein membrane transporter that is responsible for citrate extradition.”

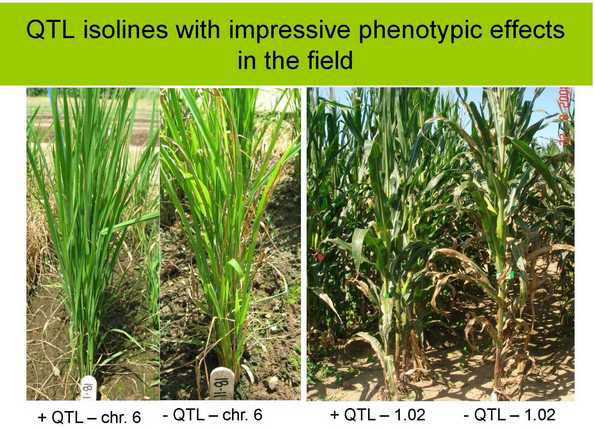

A maize field at EMBRAPA. Maize on the left is aluminium-tolerant while the maize on the right is not.

Using molecular markers, Claudia and her team of researchers from EMBRAPA, Cornell University and Moi University have developed near-isogenic lines from Brazilian and Kenyan maize varieties that show aluminium tolerance, with ZmMATE present. From preliminary field tests, the Brazilian lines have had improved yields in acidic soils.

“We identified a few Kenyan lines carrying the superior allele of ZmMATE that can be used as donors to develop maize varieties with improved aluminium tolerance,” says Claudia. “This work will also improve our understanding of what other mechanisms may be working in the Brazilian lines too.”

What has pleased Jura and other Principal Investigators the most is the leadership that African partners have taken in GCP projects.

Cherry on the cereal cake

With GCP coming to an end in December 2014, Jura is hopeful that his and other offshoot projects dealing with aluminium tolerance and phosphorus efficiency will deliver on what they set out to do.

“For me, the cherry on the cake for the aluminium-tolerance projects would be if we show that AltSB improves tolerance in acidic soils in Africa. If everything goes well, I think this will be possible as we have already developed molecular markers for AltSB.”

What has pleased Jura and other Principal Investigators the most is the leadership that African partners have taken in GCP projects.

“This has been a credit to them and all those involved to help build their capacity and encourage them to take the lead. I feel this will help sustain the projects into the future and one day help these developing countries produce varieties of sorghum and maize for their farmers that are able to yield just as well in acidic soils as they do in non-acidic soils.”

In the foreground, left to right, Leon, Jura and Sam in a maize field at the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI), Kitale, in May 2010. They are examining crosses between Kenyan and Brazilian maize germplasm.

Links

Jurandir Magalhães (pictured), or Jura, as he likes to be referred to in informal settings such as our story today, is a cereal molecular geneticist who has been working at the Embrapa Milho e Sorgo centre since 2002. “The centre develops projects and research to produce, adapt and diffuse knowledge and technologies in maize and sorghum production by the efficient and rational use of natural resources,” Jura explains.

Jurandir Magalhães (pictured), or Jura, as he likes to be referred to in informal settings such as our story today, is a cereal molecular geneticist who has been working at the Embrapa Milho e Sorgo centre since 2002. “The centre develops projects and research to produce, adapt and diffuse knowledge and technologies in maize and sorghum production by the efficient and rational use of natural resources,” Jura explains.