Something old, something new; Plenty borrowed, and just a bit of blue…

Why did the Integrated Breeding Platform (IBP) come to be, and what’s the latest offer from the five-year-old Platform? The answers are in this tell-all post on the bright and the bleak in IBP – beauty spots, blues, warts and all! Having heard on data management, breeding, and putting IBP tools, tips and services into use, let’s now take a couple of steps back and appraise the big picture: the IBP concept itself, candidly retold by an IBP old hand, in a captivating chronicle capturing the highs and lows, the drama and the humdrum, and befittingly capping our current season of IBP stories. Do read on…

We want to put informatics tools in the hands of breeders, be they in the public or private sector including small- and medium-scale enterprises, because we know they can make a huge difference”

Curtain up on BMS version 2, and back to basics on why IBP

January 2014 was a momentous month for our Integrated Breeding Platform, marking the release of version 2 of the Breeding Management System (BMS). After the flurry and fanfare of this special event, we caught up with Graham McLaren (pictured), GCP’s Bioinformatics and Crop Information Leader, Chair of the IBP Workbench Implementation Team and a member of the IBP Development Team. Graham has been intimately involved in taking IBP from an idea in 2008‒2009 to its initial launch in late 2009.

But what’s the background to all this, and why the need for IBP? Graham fills us in, explaining that in the 1980s and 1990s, informatics was the major contributor to successful plant breeding in large companies like Pioneer and Monsanto. After that, molecular technologies became the main contributors. “But to advance with molecular technologies, you need to have the informatics systems in place,” he says. “One of the biggest constraints to the successful deployment of molecular technologies in public plant breeding, especially in the developing world, is a lack of access to informatics tools to track samples, manage breeding logistics and data, and analyse and support breeding decisions.”

This is why IBP was set up. “We want to put informatics tools in the hands of breeders, be they in the public or private sector including small- and medium-scale enterprises, because we know they can make a huge difference.”

…breeders will not only find… information, but also the tools, services and support to put this information into use, in the context of their local crop-breeding projects… [the information breeders] have accumulated over the years is mostly held in their heads, in institutional repositories, or in books and published papers. There are few common places for them to share these riches and tap into those of others… IBP provides one such place.”

The script: common sense, and working wonders

Plant breeders throughout the developing world have a wealth of information on adapting crops to the challenges of their particular environments. They work wonders in their experimental fields to develop crops that help local farmers deal with pests, diseases and less-than-ideal conditions such as drought, floods and poor soils. But this valuable information they have accumulated over the years is mostly held in their heads, in institutional repositories, or in books and published papers. There are few common places for them to share these riches and tap into those of others. The Integrated Breeding Platform (IBP) provides one such place, where breeders will not only find this information, but also the tools, services and support to put this information into use, in the context of their local crop-breeding projects.

Action! Setting the stage for a forward spring, and taking a leap of faith

IBP tackles the information management issues that are at the heart of many breeding processes, goals, pursuits and problems. “Informatics problems are not crop-specific” Graham says. “What GCP is doing is to put in place a generic system for plant breeders to manage and share information. This means they can collaborate and make better decisions about strains of the crops they are breeding and that they use in their programmes. It’s setting the stage for a big leap forward in plant breeding in developing countries.”

The proposal for a crop information system applicable to a wide range of crops attracted the attention of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which provided core funding for IBP.

According to Graham, the initial five-year USD 12 million grant from the Foundation was “the biggest single investment in an informatics project in CGIAR. It was half of what was needed, and other funders joined in with the other half.” These are the European Commission and the UK’s Department for International Development.

It’s been harder than we imagined… we really needed to employ the strategies used to build aeroplanes! … some of our partners are good at solving research problems but not at developing informatics tools… Our partnership with the software company was pretty unusual…Usually, you draw up the specifications for what you want and the company comes back with the product, like giving a builder an architect’s plans and getting the keys when the building is completed. But it wasn’t like that at all…”

Collaborative construction and conundrum – going off the script, winging it and winning it

Graham describes the hurdles that the team had to overcome along the way. “It’s been harder than we imagined because of the number of partners to coordinate. It’s like building a complicated machine with many parts. The parts built by different people in different places all need to fit when they are put together. It’s so complex, we really needed to employ the strategies used to build aeroplanes!”

It’s been a matter of encouraging all those involved to do what they do best. “I’ve learnt that some of our partners are good at solving research problems but not at developing informatics tools. We were fortunate to find a private company partner to do the software engineering and to have the backing of the Gates Foundation to change our strategy along the way.”

Working with a private-sector company was a first on both sides. “Our partnership with the software company was pretty unusual,” Graham recalls. “Usually, you draw up the specifications for what you want and the company comes back with the product, like giving a builder an architect’s plans and getting the keys when the building is completed. But it wasn’t like that at all. We didn’t know exactly what we wanted in terms of the final system, learning and adapting as we went along. Fortunately, the company was flexible and worked with us step by step. We would describe to them what we wanted, they would go off and work something up, then they would come back and we would dissect it and then they would go away again and rework. This way, they produced the system we wanted. Involving a private company brought us very handsome returns for money: it meant the project could deliver on time, and on budget.”

Breeders in developing countries and small- and medium-sized companies are looking at it… a revenue stream could be secured in a win–win relationship with companies also working to develop agriculture in the developing world”

Act II: going global, and continuous improvement

Now that the alpha version of BMS has been launched, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is encouraging GCP to deploy the Platform more broadly. Graham explains, “Breeders in developing countries and small- and medium-sized companies are looking at it and, of course, they are coming up with ideas of their own. We’ve taken these on board in developing BMS version 2. In anticipation of yet more user feedback on version 2, we anticipate the third version will be released in June 2014.”

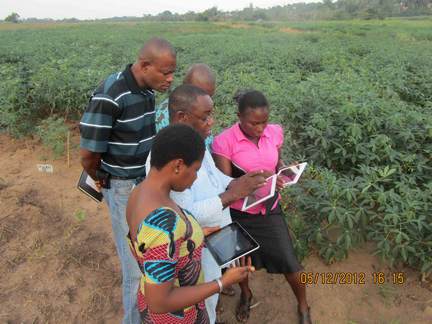

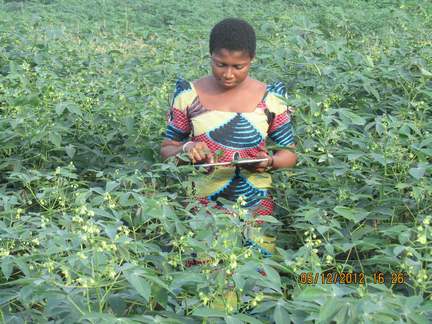

Electronic data collection at Nigeria’s National Root Crops Research Institute. GCP is promoting the use of digital tablets for data collection. See story: http://bit.ly/1fpeJON

He continues: “Deployment will involve training people to use IBP, maintaining the system and developing new tools. We’re talking to the Gates Foundation, and others, about funding for IBP Phase II. While our primary objective is to make the Platform affordable – even free – for public-sector plant breeders in developing countries, we recognise that the system needs to be maintained, supported and upgraded over the years. The question is, will small- and medium-sized plant-breeding enterprises be willing to pay for the system so that some of this maintenance and support can be recovered and the system can become sustainable in the long run? In our GoToMarket Plan, the Marketing Director is canvassing a range of companies asking what services they need and how much they would pay for them. There is a strong need for such a system in this sector and it is clear that a revenue stream could be secured in a win–win relationship with companies also working to develop agriculture in the developing world.”

Graham is convinced that rolling out IBP will have a significant impact on plant breeding in developing countries. “Because IBP has a very wide application, it will speed up crop improvement in many parts of the world and in many different environments. What this means is that new crop varieties will be developed in a more rapid and therefore more efficient manner.”

Links

- Integrated Breeding Platform

- SLIDES: Introducing the Breeding Management System

- Access the Breeding Management System

- VIDEOS: Take the IBP website tour with Graham | Other IBP videos

- IBP blogposts

- IBP podcasts – Introduction to IBP by the GCP Director | Integrated Breeding Multiyear Course (IB–MYC), with the GCP Capacity Building Leader