By Eloise Phipps

Think of something acid.

What came to mind… vinegar? Lemon juice? An acid remark? Chances are that you did not think of soil – the humble sods and clods we rely on to produce our food – unless, perhaps, you grow or breed crops.

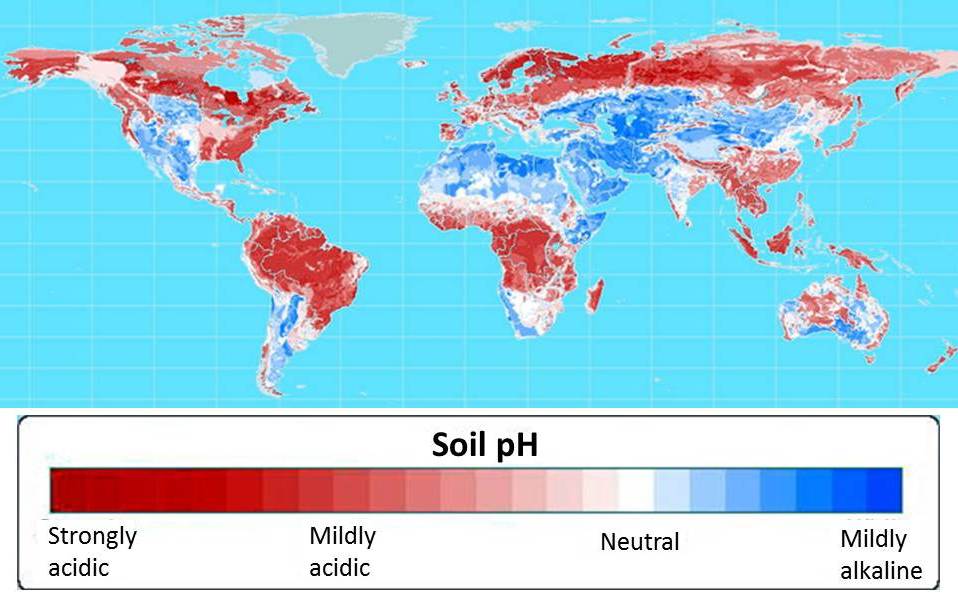

It is a cruel and surprising fact that acid soils cover almost half the land that the world uses to grow food. They can be a natural result of rainfall and soil type, but are also made worse by overuse of nitrogen fertilisers. The negative impact of acid soils on annual global harvests is second only to that of drought.

It is a cruel and surprising fact that acid soils cover almost half the land that the world uses to grow food. They can be a natural result of rainfall and soil type, but are also made worse by overuse of nitrogen fertilisers. The negative impact of acid soils on annual global harvests is second only to that of drought.

We’re getting down to earth in celebration of World Soil Day, the 5th of December – and looking forward to 2015, the International Year of Soils – as we get our teeth into this Diplodocus-sized problem, and examine how research into genes shared between different species is helping plant breeders provide farmers with crops that thrive even as the pH drops.

More than half of the world’s potential crop-growing land is highly acidic. Map courtesy of Leon Kochian.

Cretaceous crop split leaves common heritage – helping plants pass the acid test when soil dosages get dramatic

The cereal crops that we rely on for our staple foods are relative newcomers in evolutionary terms – just like humans ourselves. The species that are now maize, rice and sorghum all belong to the Poaceae family, or true grasses. They separated out and began to take their own evolutionary pathways roughly 65 million years ago – around the time the dinosaurs were going extinct. Before this, they had a single common ancestor, getting munched on by hungry Triceratops.

Because of this family relationship, maize, rice and sorghum still have many similar genes in common, often carrying out the same or similar functions in the different crops. And some of these functions can help plants do well when faced with the acid test.

The trouble with acid soils is not so much the pH itself, but the way it affects the availability of important nutrients. As acidity increases, aluminium becomes more soluble, giving plants an overdose that causes aluminium toxicity. One of the symptoms is stunted root growth – making it even harder for plants to reach other nutrients. Meanwhile, nutrients such as phosphorus become less available, stuck in forms that plants can’t absorb, making phosphorus deficiency another huge issue.

The consequences of subpar soils are far-reaching. A new report from the Montpellier Panel, ‘No Ordinary Matter: Conserving, Restoring and Enhancing Africa’s Soils’, finds that soil degradation affects two-thirds of arable land in Africa, and that without action it is likely to lock the continent into cycles of food insecurity for generations to come, and hamper both agricultural and economic development. Widespread soil acidity and its effect on nutrient availability are a key piece of the jigsaw; as the report observes, “In the more humid lowland areas [of Africa], soils are typically highly weathered, acidic and nutrient deficient.”

A Kenyan farmer prepares her maize plot for planting. Acid soils cover almost 90 percent of Kenya’s maize-growing area, and can more than halve yields.

Collaboration and gene comparison for crops that thrive when pH dives

Fortunately, our scientists are no dinosaurs. Since 2004, crop researchers and plant breeders across the world – collaborating in several GCP projects within the Comparative Genomics Research Initiative – have been using genetic knowledge at the cutting edge of science to develop local varieties of maize, rice and sorghum which can withstand acid soils’ topsy-turvy nutrient levels. Explore our comparative genomics-themed blogposts to meet our heroes Claudia, Eva, Jura, Leon, Matthias, Rajeev, Sam, and others.

Left to right (foreground): Leon Kochian, Jurandir Magalhães (both EMBRAPA) and Sam Gudu (Moi University) examine crosses between Kenyan and Brazilian maize, at the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI), Kitale, in May 2010.

What is the advantage for breeders of knowing about a gene like PSTOL1 (in the locus Pup1), which helps rice do well under low-phosphorus conditions by encouraging it to grow longer roots? Simple. Unlike the scientists in Jurassic Park, our breeders don’t need to resurrect long-dead species to get their kicks (and fortunately, they are at lower risk of being eaten by their work!). The crops they are interested already have all kinds of useful genes hidden within them, but, as with all living things, each species is tremendously varied and diverse.

This is where genomics comes in. Instead of growing many thousands of seeds to see which plants thrive, breeders can use genetic markers to look inside the seeds to see which ones have, say, Pup1. Then they only need to grow those seeds, in order to cross-pollinate them with plants with other useful traits, making the breeding process much faster and more efficient.

Screening for phosphorus-efficient rice, able to make the best of low levels of available phosphorus, on an International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) experimental plot in the Philippines. Some types of rice have visibly done much better than others.

And what makes the Comparative Genomics Research Initiative even more powerful is that it looks across related crops. Once researchers have found an acid-beating gene in one crop, they can look for similar genes in the others – turning knowledge of a single gene into multi-impact dino-mite. For example, the discovery of the SbMATE gene, behind aluminium tolerance in sorghum, spurred researchers to seek and find a similar gene in maize – which they named ZmMATE. This knowledge is now being used to breed aluminium-tolerant varieties of both sorghum and maize for Africa – and is being applied to rice too.

Maize trials in the field at our partners EMBRAPA, the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation. The maize plants on the left are aluminium-tolerant while those on the right are not.

There are many more examples of the power of comparative genomics, but the real proof will be soon to come in farmers’ fields as these new, anti-acid varieties are tested and released. The world’s poorest farmers generally cannot afford other approaches to dealing with soil acidity, such as treating soil with lime or applying extra phosphorus to their fields, so the comparative approach to cousin crops promises to be a king (or should that be Tyrannosaurus rex?) among soil solutions.

A boy rides his bicycle next to a rice field in the Philippines. With acid soils affecting half the world’s arable fields, acid-beating crop varieties will help farmers feed their families – and the world – into the future.

Links

- Explore our Comparative Genomics Research Initiative

- Meet our partners and their projects in our Comparative Genomics-themed blogposts

- Get your info straight from the horse’s (definitely not dinosaur’s!) mouth with presentations galore on SlideShare: