Scouring the planet for breeding solutions

Bindiganavile Vivek (pictured) is a maize breeder working at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), based in Hyderabad, India. For the past five years, Vivek and his team have been developing drought-tolerant germplasm for Asia using relatively new molecular-breeding approaches – marker-assisted recurrent selection (MARS), applied in a genomewide selection (GWS) mode. Their work in the Asian Maize Drought-Tolerance (AMDROUT) project is implemented through GCP’s Maize Research Initiative, with Vivek as the AMDROUT Principal Investigator.

Driven by consumer demand for drought-tolerant maize varieties in Asia, the AMDROUT research team has focussed on finding suitable drought-tolerant donors from Africa and Mexico. Most of these donors are white-seeded, yet in Asia, market and consumer preferences predominantly favour yellow-seeded maize. Moreover, maize varieties are very site-specific and this poses yet another challenge. Clearly, breeding is needed for any new target environments, all the while also with an eye on pronounced market and consumer preferences.

(1) Amazing maize and its maze of colour. Maize comes in many colours and hues. (2) Steeped in saffron: from this marvellous maize mix and mosaic, the flavour in Asia favours yellow maize.

Stalked by drought, tough to catch, but still the next big thing

Around 80 per cent of the 19 million hectares of maize in South and Southeast Asia is grown under rainfed conditions, and is therefore susceptible to drought, when rains fail. Tackling drought can therefore provide excellent returns to rainfed maize research and development investments. As we shall see later, Vivek and his team have already made significant progress in developing drought-tolerant maize.

The stark reality of drought is illustrated in this warning sign on a desiccated drought-scorched landscape, showing the severity of drought in Asia

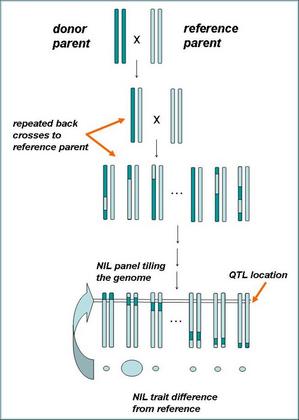

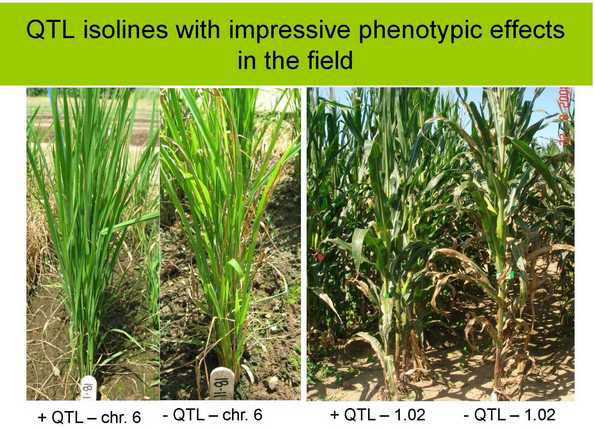

But they are after a tough target: drought tolerance is dodgy since it is a highly polygenic trait, making it difficult for plant scientists to pinpoint genes for the trait (see this video with an example from rice in Africa). In other words, to make a plant drought-tolerant, many genes have to be incorporated into a new variety. As one would expect, the degree of difficulty is directly proportional to the number of genes involved. In the private-sector seed industry, MARS (PDF) has been successfully used in achieving rapid progress towards high grain yield under optimal growth conditions. Therefore, a similar approach could be used to speed up the process of introducing drought tolerance into Asian crops – the reason why the technique is now being used by this project.

More than India: the AMDROUT project also comprises research teams in China, Indonesia, Thailand, The Philippines and Vietnam. In this photo taken during the December 2010 annual project meeting in Penang, Malaysia, the AMDROUT team assessed the progress made by each country team, and team members were trained in data management and drought phenotyping. They also realised that there was a need for more training in genomic selection, and did something about it, as we shall see in the next photo. Pictured here, left to right: Luo Liming, Tan jing Li, Villamor Ladia, V Vengadessan, Muhammad Adnan, Le Quy Kha, Pichet Grudloyma, Vivek, IS Singh, Dan Jeffers (back), Eureka Ocampo (front), Amara Traisiri and Van Vuong.

The rise of maize: clear chicken-and-egg sequence…

Vivek says that the area used for growing maize in India has expanded rapidly in recent years. In some areas, maize is in fact displacing sorghum and rice. And the maize juggernaut rolls beyond India to South and Southeast Asia. In Vietnam, for example, the government is actively promoting the expansion of maize acreage, again displacing rice. Other countries involved in the push for maize include China, Indonesia and The Philippines.

So what’s driving this shift in cropping to modern drought-tolerant maize? The curious answer to this question lies in food-chain dynamics. According to Vivek, the dramatic increase in demand for meat – particularly poultry – is the driver, with 70 percent of maize produced going to animal feed, and 70 percent of that going into the poultry sector alone.

GCP gave us a good start… the AMDROUT project laid the foundation for other CIMMYT projects”

Show and tell: posting and sharing dividends

As GCP approaches its sunset in December 2014, Vivek reports that all the AMDROUT milestones have been achieved. Good progress has been made in developing early-generation yellow drought-tolerant inbred lines. The use of MARS by the team – something of a first in the public sector – has proved to be useful. In addition, regional scientists have benefitted from broad training from experts on breeding trial evaluation and genomic selection (photo-story on continuous capacity-building). “GCP gave us a good start. We now need to expand and build on this,” says Vivek.

AMDROUT calls in on Cambridge for capacity building. AMDROUT country partners were at Cambridge University, UK, in March 2013, for training in quantitative genetics, genomic selection and association mapping. This was a second training session for the team, the first having been September 2012 in India.

Pictured here, left to right – front row: Sri Sunarti, Neni Iriany, Hongmei Chen;

middle row: Ian Mackay (Cambridge), Muhammad Azrai, Le Quy Kha, Artemio Salazar;

back row: Roy Efendy, Alison Bentley (who helped organise, run and teach on the course, alongside Ian) and Suriphat Thaitad.AMDROUT country partners are from China’s Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (YAAS); the Indonesian Cereals Research Institute (ICERI); the Institute of Plant Breeding at the Unversity of Philppines at Los Baños (UPLB); Thailand’s Nakhon Sawan Field Crops Research Center (NSFCRC); Vietnam’s National Maize Research Institute (NMRI); and private-sector seed companies in India, such as Krishidhan Seeds.Curious on who proposed to whom for this AMDROUT–Cambridge get-together? We have the answer: a Cambridge callout announced the training, and AMDROUT answered by calling in, since course topics were directly relevant to AMDROUT’s research approach.

According to Vivek, the AMDROUT project laid the foundation for other CIMMYT projects such as the Affordable, Accessible, Asian (AAA) Drought-Tolerant Maize (popularly known as the ‘Triple-A project’) funded by the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture. This Triple-A project is building on the success of AMDROUT, developing yet more germplasm for drought tolerance, and going further down the road to develop hybrids.

Outputs from the AMDROUT project will be further refined, tested and deployed through other projects”

Increasing connections, and further into the future

Partly through GCP’s Integrated Breeding Platform (IBP), another area of success has been in informatics. Several systems such as the Integrated Breeding FieldBook, the database Maize Finder and the International Maize Information System (IMIS) now complement each other, and allow for an integrated data system.

There is now also an International Maize Consortium for Asia (IMIC–Asia), coordinated by CIMMYT, comprising a group of 30 commercial companies (ranging from small to large; local to transnational). Through this consortium, CIMMYT is developing maize hybrids for specific environmental conditions, including drought. IMIC–Asia will channel and deploy the germplasms produced by AMDROUT and other projects, with a view to assuring impact in farmers’ fields.

Overall, Vivek’s experience with GCP has been very positive, with the funding allowing him to focus on the agreed milestones, but with adaptations along the way when need arose: Vivek says that GCP was open and flexible regarding necessary mid-course corrections that the team needed to make in their research.

But what next with GCP coming to a close? Outputs from the AMDROUT project will be further refined, tested and deployed through other projects such as Triple A, thus assuring product sustainability and delivery after GCP winds up.

Links

- The AMDROUT project | Photos on AMDROUT’s continuous capacity building | Capacity building at GCP

- More on the AMDROUT project – Project Updates – 2014 p 25; 2013 p 22 | Project Briefs 2013 p 13 | 2012 Annual Report

- 3.5 MIN VIDEO – why drought is such a complex customer: a perspective from rice research in Africa. Drought has to do with genetics, physiology and environment, and the interactions between these three elements.

- Maize – Research Initiative | InfoCentre | Slides | Blogposts

- Marker-assisted recurrent selection (MARS) demystified and explained (PDF)

- Vivek’s slides below

As our Maize Research Initiative does not have a Product Delivery Coordinator, Vivek graciously stepped in to coordinate the maize research group at our General Research Meeting in 2013, for which we thank him yet again. Below are slides summing up the products from this research, and the status of the projects then.